Masanori Mochida: A Pioneering Goldman Sachs Career

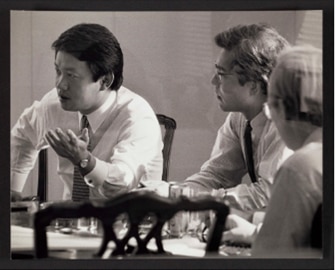

Masanori Mochida joined Goldman Sachs as an associate in the Corporate Finance Department in 1985. He is currently the president of Goldman Sachs Japan Co., Ltd., a member of the firm’s Management Committee, and co-chair of the Asia Pacific Management Committee. We asked Masa about his 35 years with the firm and the advice he would offer to those starting their careers.

Masanori Mochida joined Goldman Sachs as an associate in the Corporate Finance Department in 1985. He is currently the president of Goldman Sachs Japan Co., Ltd., a member of the firm’s Management Committee, and co-chair of the Asia Pacific Management Committee. We asked Masa about his 35 years with the firm and the advice he would offer to those starting their careers.

You joined Goldman Sachs as an associate and just celebrated 35 years at the firm. What advice would you give to someone just starting their career?

I would start by saying there is no such thing as over-preparation. In my experience, the key to success is all about confidence. Confidence is born of painstaking preparation. There are no shortcuts or fast-tracks. Practice until you reach the point of tedium. And then, prepare some more. It’s that extra mile that will set you apart from your competition.

What do you think is most important to career success?

To succeed, you don’t need a sky-high IQ score; you need staying power to see things through. In my experience, the people who are most successful are those who set goals and stick to them. That’s not to say that you shouldn’t be open to new opportunities. Being receptive to feedback is also important. I often encourage people to share any negative feedback they get from performance reviews with their colleagues, and ask their advice. It’s the surest way to grow.

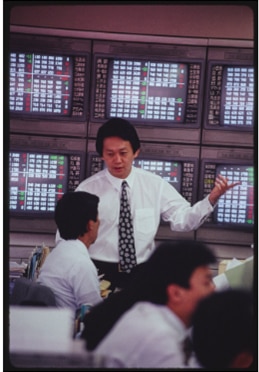

You earned your MBA from Wharton and joined Goldman after that. What was the industry like back then?

Well back then—remember it was Japan in the 1980’s—the financial industry was dominated by local players. US banks had made some inroads into the market. However, they were regarded very much as outsiders run by ex-pat bankers and with limited local autonomy. I saw an opportunity for Goldman Sachs, which opened its first office in Tokyo in 1974, to become the premier investment bank in Japan. The mission to accomplish this was, and remains, my motivation for being with the firm. We have achieved many milestones, but we still have opportunity ahead of us.

Tell us about the process of building Goldman Sachs in Japan.

Japan has very particular business practices and customs—and to be truly successful here you have to respect these cultural aspects. Take deal-making as an example. In the US, there may be three or four people with the final say on executing a transaction. But in Japanese companies, that number is more likely to be between ten and fifteen. This reflects a Japanese cultural preference for sharing responsibility for business decisions rather than consolidating them.

I knew from early on that localization would be the key to Goldman Sachs’ success in Japan. So we focused on putting together a team of Japanese and Japanese-speaking professionals who could deliver all that the firm’s international network has to offer, while servicing our clients in the manner they expected of a Japanese firm.

Perhaps because our meritocratic culture was something of a rarity at the time in Japan, we have been fortunate to have our most talented people remain with the firm over the years, so much so that our Japan management team is comprised almost entirely of locally hired professionals who know this market the best. This is a key point of differentiation from our international peers.

There’s a story about your appointment as head of Goldman Sachs Japan in 2001. Can you share?

Back then, I was an investment banker and my passion was all about chasing deals. I was not keen on taking on management responsibilities even though I thought I could be asked. Our CEO at the time, Hank Paulson, offered me the position—and I expressed my deep reluctance. Well, Hank—who went on to become the US Treasury Secretary—was greatly disappointed with my response. He told me that it was time to stop thinking about myself and to start thinking about what I could do for the firm.

I was mortified. And, upon reflection, I knew he was right—I was being self-centered to not accept the role. I did accept, and to be honest, I’ve never changed so much in my life as I did then. It was from this experience that I learned that in order to change and grow to your full potential, one must always let something go.

Thinking about today—what are your thoughts on the current pandemic and any lasting impact?

This crisis is unlike anything I have seen in my career. Clearly the pandemic is acting as a catalyst for the further digitization of society and changing the workplace and the world as we know it.

However, as someone with over three decades in this industry, I realize that change and crisis are just part and parcel of being in this business. For that reason, I believe leaders should not worry too much about predicting the future. Just keep a cool head and an analytical eye and focus on building an organization that is supple and flexible enough to adapt to change. It’s most important to continue to support and advise clients as they navigate this environment. That’s what we focus on doing. Everything else will work itself out.

What is your focus outside of work?

It’s perhaps not that widely known outside of Japan, but one in seven children in this country lives in relative poverty. Through Goldman Sachs Gives, our charitable foundation, I’ve worked with various organizations on initiatives to combat this problem, and I am particularly grateful to have had the opportunity to help fund the construction of two children’s homes in the outskirts of Tokyo, together with other senior members of the Japan office.

My most recent project was inspired by the need to provide more jobs for young people. That eventually led to me purchase a plot of land in Kyoto where I’m building a large flower garden. The entry fees will be donated to organizations that are fighting child poverty, and I hope that we’ll be able to employ youngsters who are struggling to find work.

My interest in this issue is not just philanthropic. Japan has a rapidly aging and shrinking population. Helping disadvantaged youngsters find a way out of poverty and into productive work is at the same time helping boost the economy and adding to the nation’s shrinking taxpayer base. In short, investing in alleviating child poverty is an investment in the future of Japan.