The UK Performs Poorly When it Comes to Social Mobility. Here’s How it Can Improve

The article below is from our BRIEFINGS newsletter of 07 April 2022

Compared with other countries, the most disadvantaged in the U.K. are less likely to climb the income ladder and the economically advantaged tend to stay at the top. Covid-19 has increased inequality further, and recent rises in inflation, especially energy costs, are intensifying the problem. In a recent report, Goldman Sachs Research has taken a closer look at the issue, investigating what needs to be done to improve mobility and opportunity for people in the U.K. We sat down with authors of the research, Goldman Sachs’ European Strategist Sharon Bell and Chief U.K. Economist Steffan Ball, to discover more.

Could you start by defining what social mobility is?

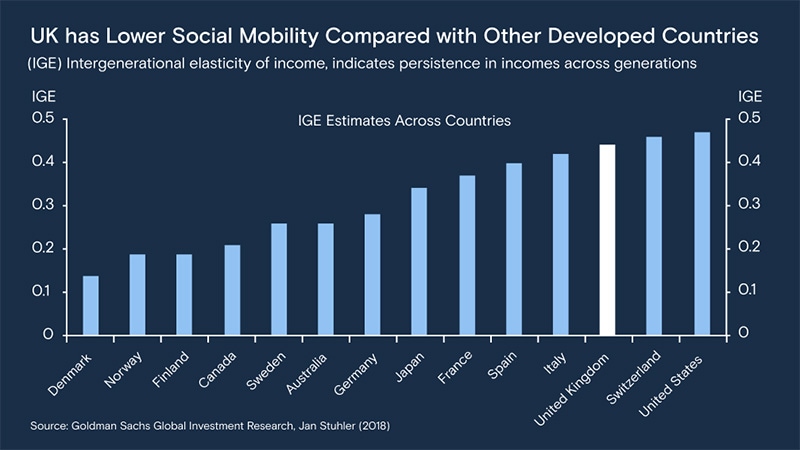

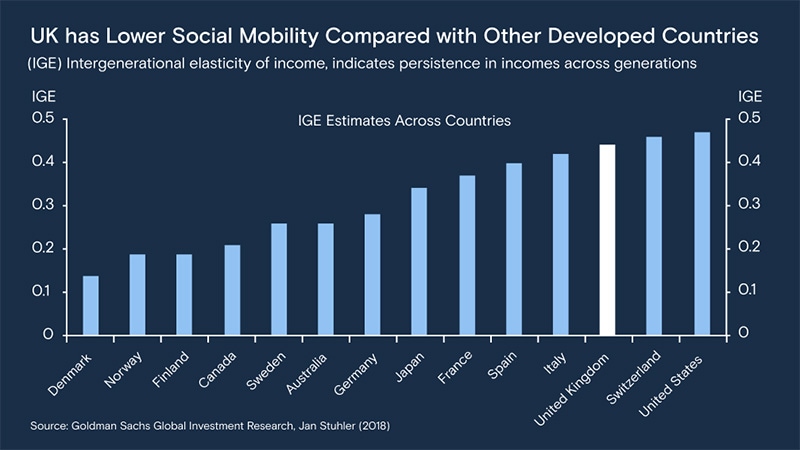

Steffan Ball: Put simply, it means doing better or worse in terms of lifetime outcomes than your parents. If you look at the U.K. and compare it with other developed countries, it stands near the bottom of the international league table for both social mobility and inequality. It’s important to clarify that the two things are slightly different. For example, you can live in a very unequal society but still have a very different life outcome to your parents.

On social mobility, political debate is often focused on who climbs up the social ladder and that is critical. But it should also consider whether better off families retain their social and economic position. And on this metric too, the poorest and the richest in the U.K. are the most socially immobile. So this exacerbates social inequalities. Only the U.S. and Switzerland have lower social mobility than the U.K.

Sharon, this is a relatively new area of research for Goldman Sachs. What would you say are the key takeaways from ‘The Bigger Picture: UK Social Mobility – A Tough Climb?’

Sharon Bell: The primary thing is that the U.K., relative to the rest of Europe, looks pretty poor on most metrics on social mobility and things have actually deteriorated further in the last few years. The pandemic has made it worse; potentially the energy spike we are seeing will also make it worse. So the U.K. scores very poorly on most social mobility metrics and the key takeaway from our report is that there are things governments, policymakers and corporations can do to help address the problem. I feel that social mobility, as a particular diversity target and interest, is something that is more nascent than other areas (such as gender for example) and something which is also incredibly important given that it’s already a wide gap and gotten worse.

Why is the U.K. performing so badly on social mobility and has the situation been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic?

Steffan Ball: There is actually very little consensus on causes of the U.K.’s relatively poor performance both on social mobility and inequality metrics. Some researchers have argued that’s it’s due to a combination of strong education transmission from generations to generations and, added to that, the significant earning premium for graduate level jobs. A second explanation has been the large regional income differences we have in the U.K. and the growth of higher paying service sector jobs, particularly in the South. Finally, other researchers have noticed that the more progressive tax systems in some countries such as Denmark, Finland and Norway often lead to higher social mobility. And in the U.K., it could be that the tax system is disadvantageous to inequality and mobility.

Undoubtedly, the pandemic has increased inequality further and there is survey evidence to show this. YouGov did a report not so long ago and it showed over half - 56% - of the U.K. population felt Covid-19 had increased social inequality. This is consistent with the impact you see in the labor market. Covid-19 has had a larger impact on lower income jobs as they tend to be consumer facing rather than office based. These lower income jobs were more likely impacted by government lockdowns, while office jobs could be done remotely more easily.

Surveys also show a big regional difference. People in the North of England tend to say they have experienced harsher conditions recently than people in the South – particularly for employment and education. Survey evidence compiled by the Social Mobility Commission shows that 35% of people living in the North said Covid-19 had a detrimental impact on employment, whereas only 17% in the South did. On education: 21% in the North thought that they suffered more during the pandemic in terms of education outcomes, whereas only 8% of people thought that was the case in the South. More recently, rising energy prices are a concern, because they have a large impact on the households at the bottom of the income distribution and these people also tend to have little to no saving buffer as well.

How can social mobility be improved in the U.K.?

Steffan Ball: In the report we highlighted four main policy areas for improvement. The first one is improving geographical inequality by increasing public investment in less well-off regions of the U.K. The second is education and in particular focusing education on equalizing opportunities and improved access for children from lower income households. The third policy area is apprenticeships and retraining programmes that are retargeted toward people from disadvantaged backgrounds. And finally, high quality digital access for less wealthy households, in particular those living in more remote locations.

To what extent can the corporate world play a positive part in improving social mobility and inequality in the country?

Sharon Bell: The corporate sector can have quite a huge influence in the U.K. Who businesses choose to hire, who they decide to train, what safety nets they give people in terms of pay, healthcare, pensions, other benefits—all of those things are incredibly important. Also, how businesses invest and where they invest is so crucial. Are they investing offshore or are they investing onshore? Are they investing in a U.K. workforce or not? Are they just concentrated in one location, like London, or are they looking outside that?

I would put it into three buckets in terms of what companies can do to help improve social mobility: The first one is that they can do things internally. They should think of social mobility as part of the diversity spectrum. So they can look at the social backgrounds of their employees and think more broadly about their talent pool. It’s about looking for diversity of thought and not just picking from one area of the community. That’s the first and crucial thing.

Second, I do think some companies are operating in fields that will help social mobility by the very nature of what they do. For example, you have real estate companies, insurance companies, investment funds that are investing in infrastructure projects in the North of England or in social housing or social impact funds. It’s about using money in specific ways that will help to invest in underinvested communities. For example, are telecoms companies providing connectivity to everyone at good speeds now? Are tech companies making digital education as accessible as they could be? Maybe it’s not some of these companies’ main objectives but, as part of their business, they can help social mobility.

Finally, the last area where businesses could be important is ESG investing. We tend to focus a lot on the E: the environment. We argue that there should be more focus on the S. ESG funds should be thinking about the social impact of companies. So companies that are having a good social impact should be seeing flows from ESG funds buying their equity and buying their debt, which will reduce their cost of capital and allow them to invest more in having a positive social impact.

- The Bigger Picture: UK Social Mobility - A Tough Climb24 February 2022

Subscribe to Briefings

Our signature newsletter with insights and analysis from across the firm

By submitting this information, you agree that the information you are providing is subject to Goldman Sachs’ privacy policy and Terms of Use. You consent to receive our newsletter via email.