How Deep Could the Next US Recession Be?

If the U.S. economy slips into a downturn in the next year, there’s at least one consolation: the contraction isn’t expected to be deep, according to Goldman Sachs Research.

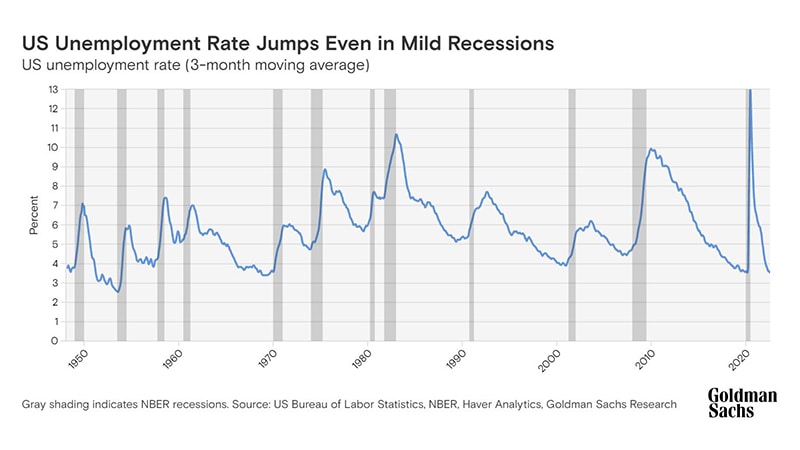

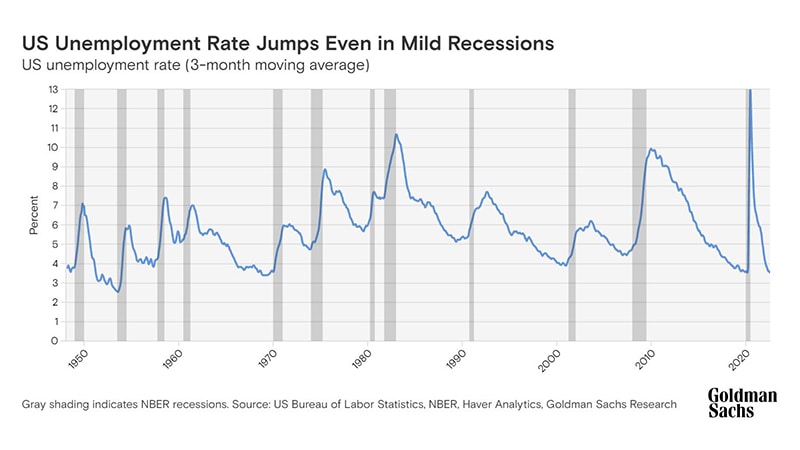

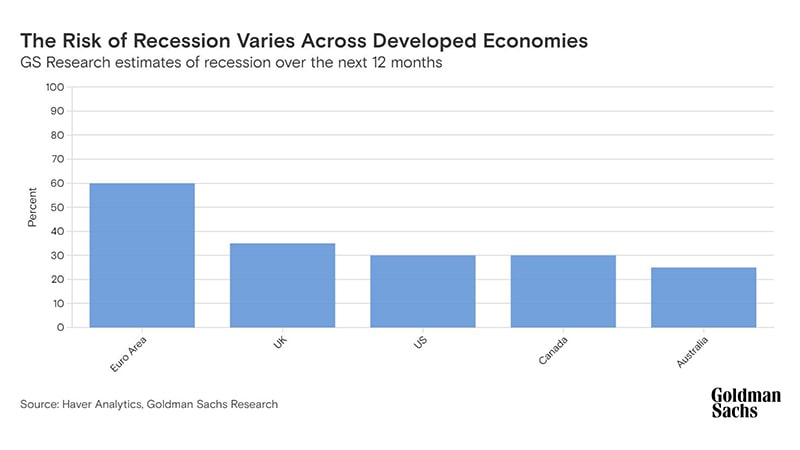

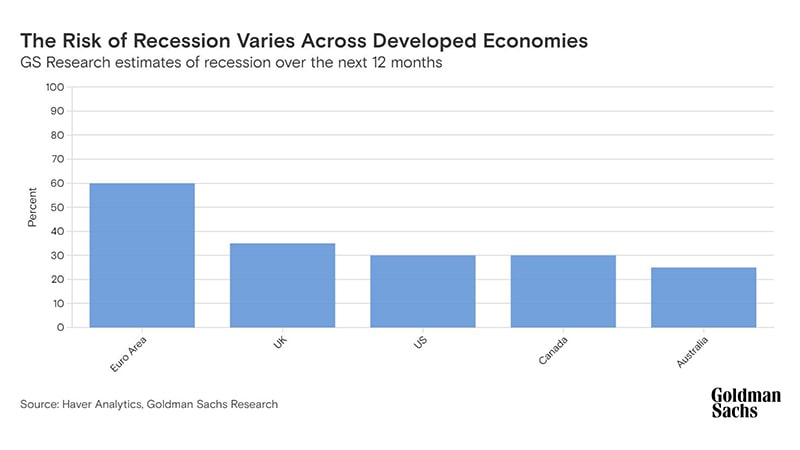

The likelihood of a recession happening in the U.S. in the next 12 months is now at about one in three, according to GS Research. With those odds, it’s reasonable to consider how severe a potential recession could be. Even in the two mildest postwar downturns in the U.S., in 1960-61 and 2001, unemployment increased by about 2 percentage points.

However, economists at GS Research expect any post-COVID U.S. recession to be mild, with a limited increase in the unemployment rate of around 1 percentage point. This would be unprecedented in postwar U.S. history, though recessions with similarly limited increases have occurred in other G10 economies.

There are three reasons a downturn during this unusual post-pandemic cycle isn’t likely to be severe.

First, there are still more jobs than workers to fill them. And even if the Federal Reserve slows down demand, causing employers to scale back staffing, the imbalance between available jobs and workers should absorb much of that contraction without triggering a large rise in unemployment. “Recent preliminary evidence suggests this is possible,” our senior global economist Daan Struyven says. “In fact, the U.S. job openings rate has declined by 0.7 percentage points since March while the unemployment rate has actually declined by 0.1 percentage points. This suggests that the slowdown in output growth is likely to have a smaller-than-usual effect on employment, which tends to drop sharply in traditional US recessions.”

Second, even if job growth ends up slowing substantially, consumers likely won’t feel the full economic shock of this decline. In fact, a downturn in hiring that coincides with sharply lower inflation could be a net positive for spending, Struyven explains. “While slower job growth will likely weigh on real disposable income growth, sharply lower headline inflation in areas such as gasoline and durable goods could support real disposable income growth, which has now likely bottomed,” he says.

Moreover, the strength of private-sector balance sheets (partly built up through the pandemic) — among households, businesses and banks — could dampen spillovers from any potential real income weakness into spending by consumers during an incoming recession.

Finally, and perhaps most fundamentally, Struyven says there are still clear drivers of growth across the U.S. economy. Consumer spending still hasn’t returned to its pre-pandemic trend and certain COVID-sensitive service sectors still have substantial room to normalize. The key industries with room to grow are tourism and office work-related consumption (e.g. transport services and dry cleaners.) On top of that, climate-related spending and infrastructure investment are likely to continue growing too, aided in part by long-lasting federal spending programs.

Risks of a deeper recession in the U.S. will increase if inflation proves to be more entrenched than anticipated or the economy is hit by additional negative supply shocks, Struyven says.

Private sector strength and incomplete pandemic recovery (room for growth) might also reduce the severity of recessions elsewhere. And similar to the U.S., countries like Australia and Canada have unusually high job opening numbers, which could help dampen any negative economic hit in those economies.

Recession risk from country to country is inevitably more nuanced, but the evidence for countries and central banks that started hiking policy rates early is encouraging. GS Research examined nine economies that began to tighten policy aggressively by October 2021 and none of them show clear evidence of full-blown recession yet, as unemployment rates largely continue to decline. Those countries may still enter a recession, and whether Peru and Chile are now in a mild recession is a close call, but the overall resilience of these early hikers supports the idea that no major economy will enter a monetary policy-driven recession over the next year.

“The early hikers are largely emerging market economies and it is still too early to tell whether they will enter a recession,” Struyven says. ”That being said, the drivers of their resilience — strong balance sheets, room for reopening, and pent-up demand for workers — are factors that will remain globally relevant.”

Answers on recession risk are less clear for Europe. GS Research’s central forecast is that the euro area will experience a mild recession, with annualized growth of -0.3% and -0.6% in Q3 and Q4 of 2022. And while there is still substantial room for a boost from services reopening in southern Europe — especially in Spain — energy security and its contribution to inflation continue to be a defining factor for the continent. Gas supply disruptions, increases to energy prices and supply-chain issues could make the euro-area recession much deeper.

Our signature newsletter with insights and analysis from across the firm

By submitting this information, you agree that the information you are providing is subject to Goldman Sachs’ privacy policy and Terms of Use. You consent to receive our newsletter via email.