Wage Inflation in the US May Have Already Peaked

Jaws dropped when the latest report on consumer price inflation arrived, clocking its biggest year-over-year jump in the U.S. since 1981. That and other economic data points contributed to the Federal Reserve’s decision on June 15 to make its biggest rate hike since 1994. But there are signs that labor shortages — a key driver of overall inflation, may have peaked months ago, according to Goldman Sachs Research.

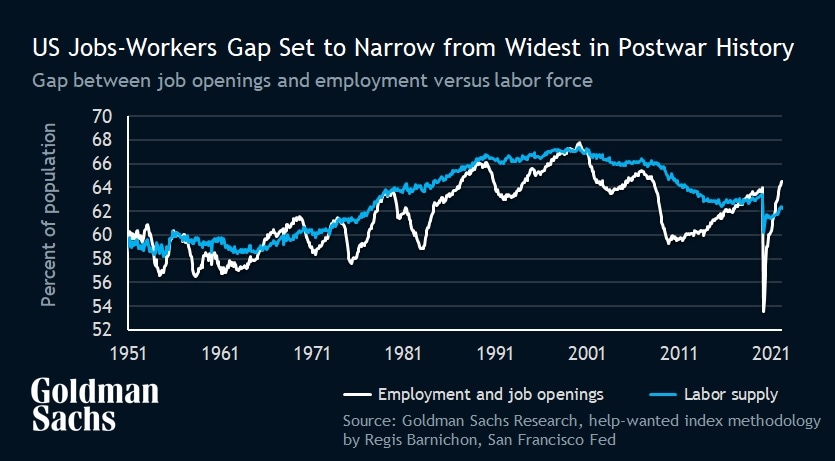

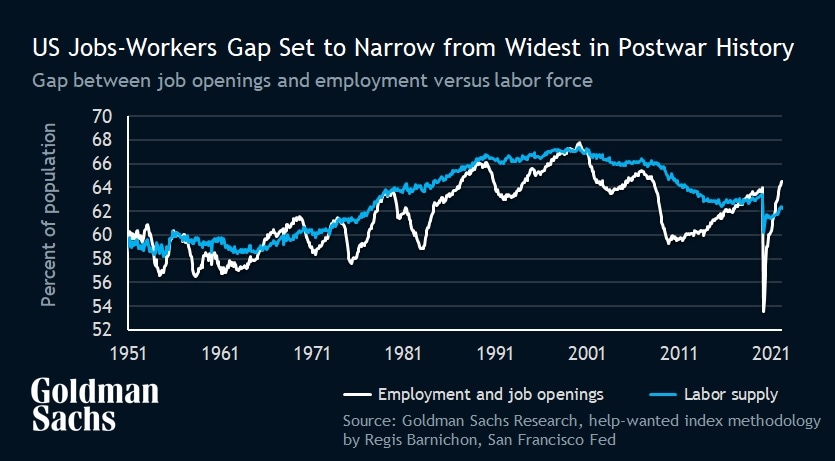

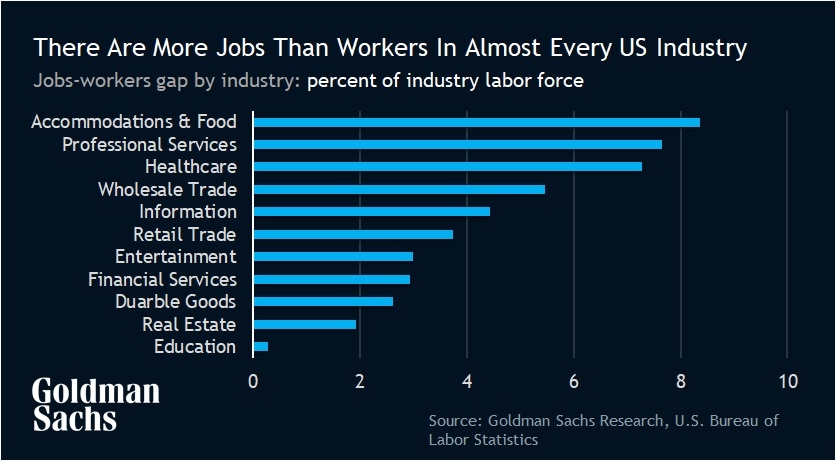

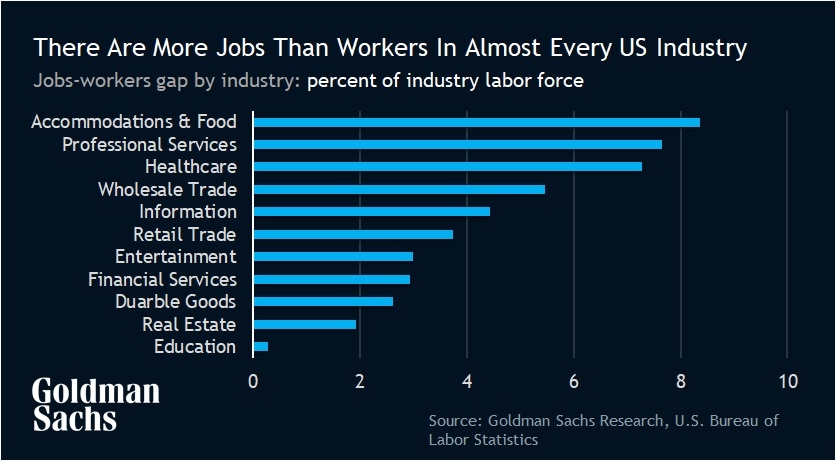

The shortfall in workers may have peaked at “an extremely elevated level” in March, according to Daan Struyven, co-leader of research on the global economy at Goldman Sachs in New York. Since then the jobs-workers gap — which is the difference between the total number of jobs (in other words, employment plus job openings) and the total number of workers — has started to edge down. Struyven says this metric is the best predictor of wage growth.

“It’s very intuitive for capturing the balance of the bargaining power of workers versus employers,” Struyven says. “If there are a lot of vacancies and very few people who are looking for a job, that suggests workers have the upper hand and bargaining power and that should put upward pressure on wage growth.”

Wage growth is a critical part of overall inflation, and it’s also the piece that the Fed can influence. While the central bank has little to no impact on global goods and commodity prices, the Fed is able to slow economic activity and employment growth by raising short-term interest rates and tightening financial conditions. The services sector is especially labor intensive, and wages are two-thirds of the cost structure in the U.S. economy. “That’s why it’s intuitive that wages are a key driver of the outlook for inflation,” Struyven says.

Economists at Goldman Sachs started paying closer attention to the jobs-workers gap in part because traditional measures of labor market tightness were out of synch with the surge in pay in the U.S. and other developed countries, Struyven says. The unemployment rate in the U.S., for example, is still slightly higher than it was before the pandemic (3.6% in May versus a low of 3.5% in 2019). Taken by itself, that rate would suggest the job market isn’t overheated.

But red-hot wage increases tell another story. The jobs-workers gap shows that the American employment market is hovering around its tightest level since World War II. This measure has shown more statistical significance with wage growth and more accurate recent predictions than standard measures like the unemployment gap or the prime-age employment to population ratio, according to Goldman Sachs Research.

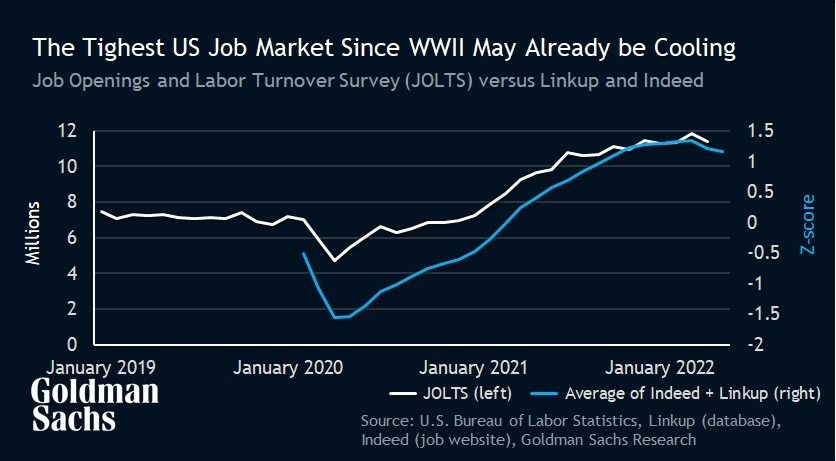

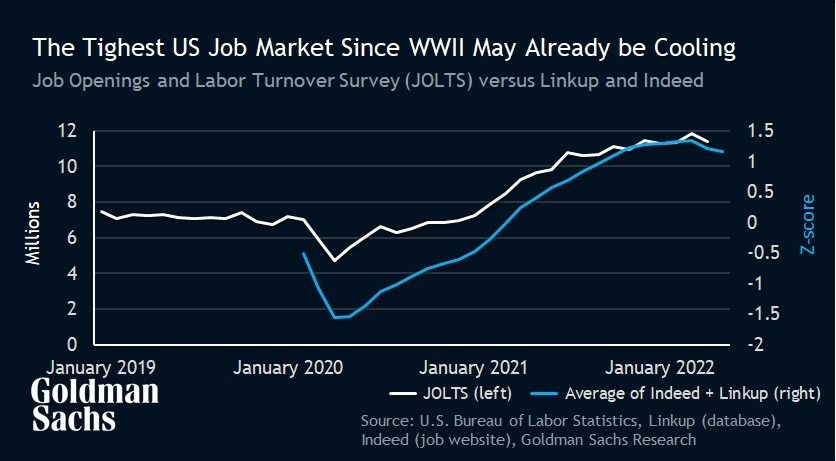

While shelter inflation has risen further, there are other measures that also suggest that the labor market and underlying inflation pressures have begun to moderate in the U.S. The unemployment rate has been stable for three months, and payroll growth has slowed from about 600,000 jobs per month during the winter to about 400,000 per month recently. Job vacancies fell in April, according to the Department of Labor’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). Alternative data suggests that job openings declined further in May and June.

Separately, there are signs that supply-chain bottlenecks, another key contributor to inflation, are easing; Goldman Sachs transportations analysts’ supply chain congestion index has fallen to levels not seen since last summer.

There may be a number of reasons the jobs-workers gap has increased so much, including heavy fiscal spending as developed countries sought to counterbalance the disruption from the COVID pandemic as well as reduced immigration and a reduced labor force. The jobs-workers gap has risen in all Group of 10 advanced economies except Japan since the fourth quarter of 2019, says Struyven, a former economist at the World Bank.

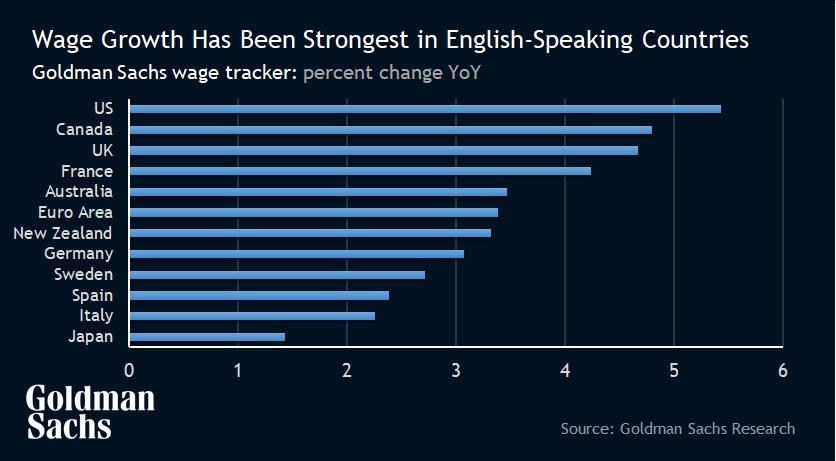

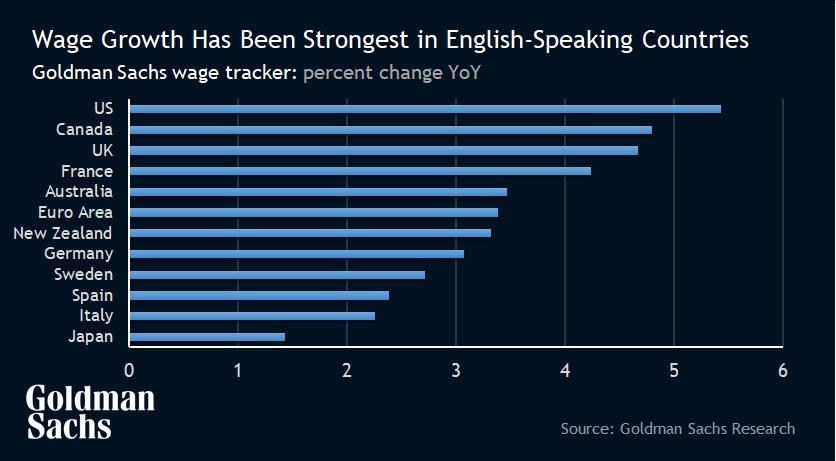

The jobs-workers gap also helps economists understand why wage growth has been higher in the likes of the U.S. and U.K. — where the gap has increased a great deal — than in other advanced countries. English-speaking countries tended to have a stronger fiscal response to the pandemic, and they also had central bank policy rates before the pandemic that were above zero (unlike the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan), which likely gave their economies an extra boost when policy makers slashed interest rates.

Fed chair Jerome Powell is focused on the balance of labor, and that’s one of the reason why policy makers have hiked rates so aggressively. The central bank in Washington raised rates by 75 basis points this month after previously signaling that increases of 50 basis points were likely. Powell is also concerned about headline inflation and consumer expectations for price increases; as the Fed has become increasingly hawkish, Goldman Sachs Research now forecasts a 48% probability of recession during the next two years (up from an earlier forecast of 35%).

“One of the key takeaways from the last Fed meeting is that Powell and the Fed are willing to soften the labor market,” Struyven said. “They don’t want to generate a recession, but the priority is to bring inflation down. Once inflation expectations become unanchored you have high unemployment for a very long time.”

Subscribe to Briefings

Our signature newsletter with insights and analysis from across the firm

By submitting this information, you agree that the information you are providing is subject to Goldman Sachs’ privacy policy and Terms of Use. You consent to receive our newsletter via email.