Will the US go into recession?

Can the Federal Reserve slow the U.S. economy enough to bring down inflation without causing a recession? It’s a delicate balance, but there are several reasons that it could be more achievable than in the past, according to economists at Goldman Sachs.

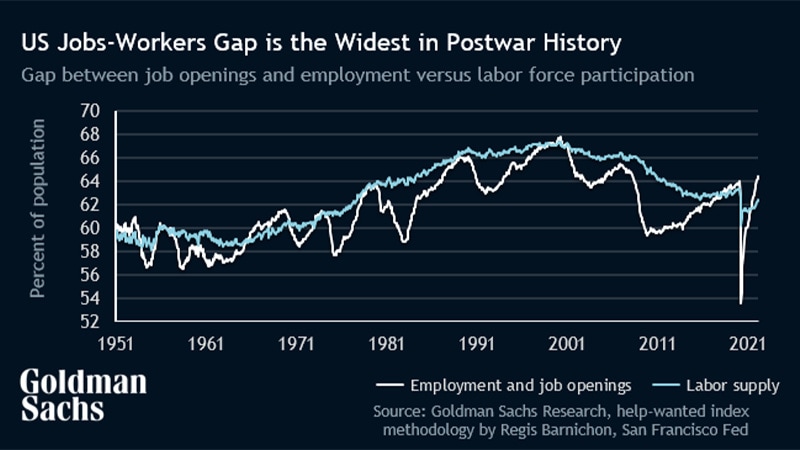

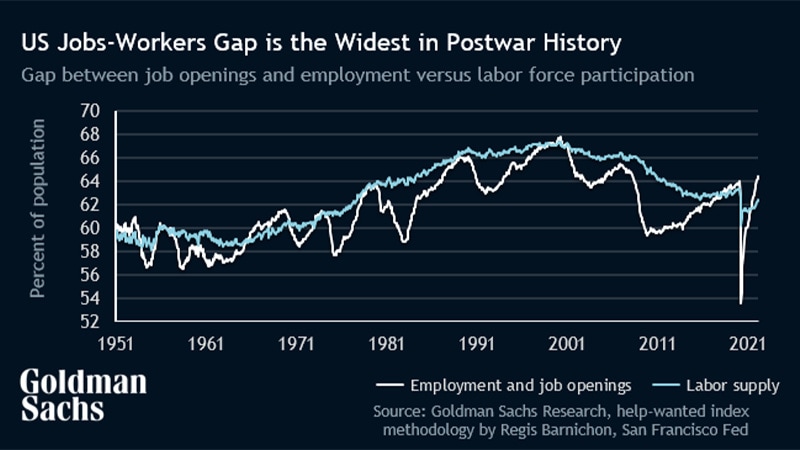

Goldman Sachs Research’s jobs-workers gap is a key metric for this analysis: the difference between the total number of jobs (in other words, employment plus job openings) and the total number of workers, at more than 5.3 million, shows that the labor force is at its most overheated level in postwar history.

Goldman Sachs economists consider this measure a better indicator of labor market tightness because it includes open positions in addition to current employment when gauging labor demand, and because it uses raw data and doesn’t require an estimate of the natural level of unemployment, according to a report by Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs. This measure has shown more statistical significance with wage growth and more accurate recent predictions than standard measures like the unemployment gap or the prime-age employment to population ratio.

While it’s hard to say with precision, the jobs-workers gap needs to shrink by about 2.5 million (roughly 1% of the adult population in the U.S.) in order to cut wage growth from its pace of around 5% to 6% to about 4% to 4.5%, according to estimates by Goldman Sachs Research. That would be consistent with the Fed’s inflation forecast of around 2% to 2.5% for the next two years.

For the Fed, that means damping the outlook for growth just enough to get companies to put some of their expansion plans on hold and close some open positions — but not so much that they slash output and lay off workers. To achieve that goal, growth in gross domestic product would need to slow to about 1% to 1.5% for a year, which is weaker than the (below consensus) 1.9% that Goldman Sachs economists have forecast (fourth quarter, year over year).

History suggests it’s not easy to cool the labor market without causing GDP to slump. The U.S. unemployment rate has never gone up by more than 0.35 percentage point (on a three-month average basis) without the economy going into a recession. Once the labor market has overshot full employment, the path to a soft landing becomes narrow, according to Goldman Sachs economists.

Even so, Goldman Sachs Research expects the U.S. to avoid a contraction for several reasons:

- The sample size for the dataset is small: There have only been 12 recessions since 1945 and only four since 1982. Some non-U.S. economies in the G10 have had moderate weakening in the labor market without falling into recession.

- It should be easier to reduce the jobs-workers gap during this cycle than in the past because the employment market is still normalizing after COVID disruption, which Goldman Sachs Research expects will add as many as 1.5 million workers to the economy in excess of normal population growth. And unlike laying off workers, closing open positions doesn’t have negative second-round effects that ripple through the economy.

- Households are in better shape financially than they have been at the onset of most recessions. The ratio of household-net-worth to disposable income is at a record high, the personal savings rate is elevated, pent-up savings are ample and Americans overall have a healthy financial surplus. This means a slowdown in labor income growth is less likely to cause households to sharply cut back on spending than in some past cycles.

All that said, historical patterns deserve some weight and the overheated job market has caused a meaningful increase in the risk of recession, according to Goldman Sachs economists. As a result, they assign roughly 15% odds to a recession in the next 12 months and 35% within the next 24 months.

Subscribe to Briefings

Our signature newsletter with insights and analysis from across the firm

By submitting this information, you agree that the information you are providing is subject to Goldman Sachs’ privacy policy and Terms of Use. You consent to receive our newsletter via email.