The global credibility gap: Assessing underperformance and overreach in today’s geopolitics

Jared Cohen is president of Global Affairs and co-head of the Goldman Sachs Global Institute.

Ian Bremmer is president & founder, Eurasia Group and GZERO Media.

Executive Summary

- Today’s geopolitical shocks are connected by a great-power credibility crisis. It is increasingly apparent that neither the United States nor China is both willing and able to singlehandedly uphold the international order. This crisis of credibility is compounding geopolitical instability and uncertainty.

- Great-power credibility is a function of economic position, military strength, diplomacy, history, reputation, and context. The US has not lost significant power in recent years, but its credibility has diminished, whereas China has gained significant power but not the credibility to match it.

- The US remains the world’s leading power, and the international order as we have known it rests on US credibility. The US’s credibility has been challenged by China’s rise, recent foreign policy choices, and domestic political division and dysfunction.

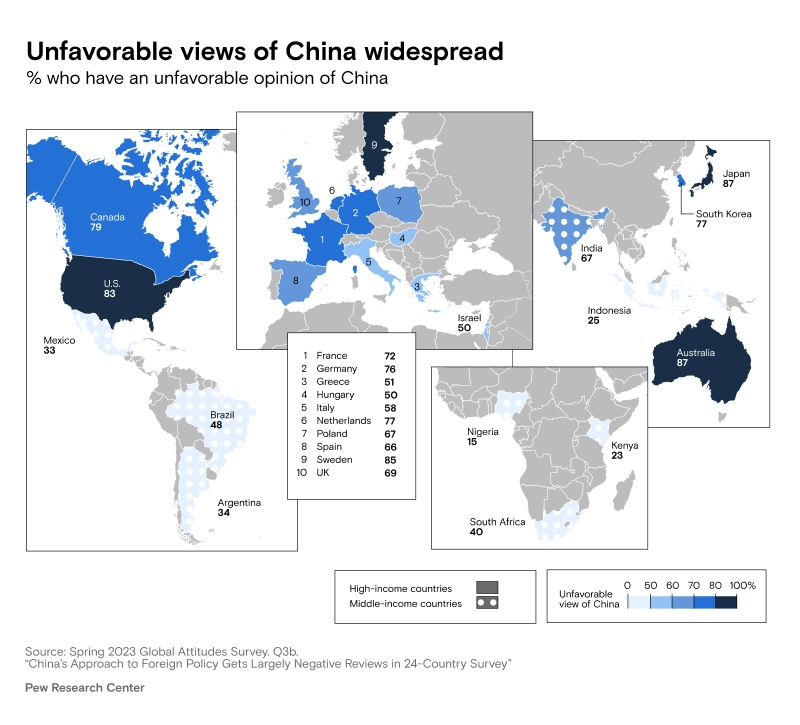

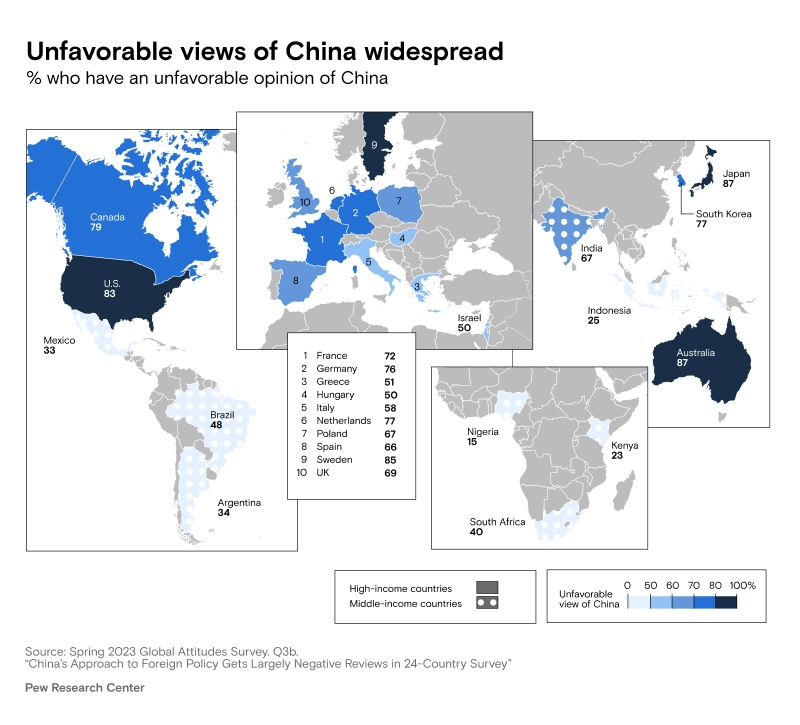

- China — an aspiring global leader — is facing a different credibility crisis, driven by the risk of a middle-income trap amid a historic economic slowdown and increased focus by Beijing on political control over economic growth. Meanwhile, China’s military buildup and modernization, coupled with increased regional aggression, is increasing concerns about its global ambitions. While it maintains favorable relations in much of the Global South, unfavorable views of Beijing have risen around the world in recent years.

- A world of heightened political and even ideological difference is, in our view, here to stay – centered on the strategic competition between the United States and China.

- The ongoing credibility crisis is changing geopolitics in profound ways, challenging existing institutions and creating space for the emergence of new international actors:

- Geopolitical swing states – Relatively stable countries that have their own global agendas independent of Washington and Beijing, and the will and capabilities to affect everything from supply chains to capital flows.

- A world of shifting alignments – New forms of international cooperation based on geography, interests, and values. Where existing multilateral arrangements are seen as less credible, or not fit for purpose, new groupings are attempting to fill the void.

- The technopolar order – The world’s biggest private technology companies are stepping into the breach to play larger, more autonomous roles in global politics. Many of these companies exercise near-sovereign powers over digital space and are increasingly challenging nation-states as geopolitical actors.

- Global governance deficit – The erosion of international cooperation on transnational challenges that require collective action, from pandemics to climate change to mitigating the risks and seizing the opportunities of disruptive technologies.

- For countries and companies, assessing the credibility — or lack thereof — of the world’s leading powers provides important insights to assess where countries will act as expected, where they will overreach, and where they will fall short of their stated objectives. In an unpredictable world, the credibility lens is a vital tool to anticipate what could come next.

Introduction

Washington and Wall Street are worried about the same thing: geopolitics. After decades of relative international stability and increasing globalization, businesses and governments are now struggling to understand a new, more unpredictable, and more violent global reality. Foreign policy now matters for businesses, and businesses matter for foreign policy. For firms and investors, concerns about this dynamic are only growing. And for today’s leaders in every field, few questions are more important than how to manage geopolitical risks.

That is no easy task. In the last few years, relations between the world’s two leading powers, the US and China, have deteriorated so sharply that many commentators argue — incorrectly, in our view — that Washington and Beijing are engaged in a new Cold War. Although largely in the rearview mirror, the Covid-19 pandemic unleashed political and economic shocks that are still reverberating across the global system. Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 plunged Europe into a destabilizing war that continues to have far-reaching consequences for trade and markets worldwide. And in October 2023, Hamas terror attacks against Israel sparked a new Middle East war that not only changed Israel and Gaza, but also threatened to undo broader regional trends toward economic transformation and geopolitical stability.

These global shocks are connected. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) economists, they are among the drivers of a “policy-driven reversal of global economic integration” termed “geoeconomic fragmentation.” For some analysts, they are constituents of a “polycrisis,” in which a series of disparate shocks “interact so that the whole is even more overwhelming than the sum of the parts.” This coincides with the emergence of technologies like artificial intelligence that promise to transform industries and society. Against this backdrop, the White House has repeatedly highlighted how competition with China, the pandemic fallout, the war in Ukraine and other conflicts have led to a “new Washington consensus” — endorsed in many other capitals as well — about the links between national security and economic policy.

Today’s geopolitical shocks also didn’t occur in a vacuum. They’ve collectively revealed and are exacerbating a growing crisis of credibility in the international system as it becomes increasingly apparent that no power is both willing and able to singlehandedly uphold the international order. This global credibility gap, in turn, is compounding geopolitical instability and uncertainty.

At the core of this paper is a concept to help leaders navigate that reality — credibility. We discuss what it is, who has it, and how it shapes geopolitical outcomes. Though difficult to measure, credibility matters in international relations, and it matters most in an unpredictable world. Understanding credibility can help policymakers and investors lead in an era in which geopolitical stability — and a stable business environment — can no longer be taken for granted.

The credibility lens

Interactions between states depend on the realities and perceptions of power, which are in turn correlated with countries’ capabilities and credibility — whether other actors believe they will deploy their capabilities effectively, neither underperforming nor underreaching.

For states, credibility involves several key variables: hard military and economic power; the soft power of political and cultural attraction; and more intangible qualities related to trustworthiness, history, and context. Hard and soft power are necessary but not sufficient for a state to be credible; others must also believe that it will follow through on commitments and meet expectations.

In its everyday meaning, credibility is whether someone or something is trusted or believed — whether they can be relied upon to follow through on their promises and make good on their threats. The same holds true for states, especially great powers, and the regional and international orders that they shape. If an order lacks credibility, its detractors — and even disillusioned adherents — cease to abide by established rules and conventions. The result, unsurprisingly, is disorder and instability of the type we are witnessing today.

Why credibility matters

The international order is less stable today than it has been at any point since the Cold War. To understand what that means and where we may be headed, credibility is a key variable that allows leaders from every sector to navigate the world as it is. It’s a way to see where the institutions and standards underpinning the international order are holding and faltering; what new institutions, alignments, and leaders are likely to emerge; and where conflicts between these two trends will be most severe.

Credibility is the leverage that allows states to turn power into influence. States use threats and promises to deter adversaries, reassure allies and partners, and compel actions. But carrying out threats and making good on promises is costly. As a substitute for coercion, credibility allows states to achieve their desired outcomes at minimal cost to themselves, allowing them to advance their priorities beyond what raw hard and soft power alone would allow. As former US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates observes, successful deterrence “depends on the certainty of commitments and constancy of response,” whereas an “erratic and unreliable” state invites challenges from its adversaries and skepticism from allies and partners.

Although policymakers often conflate the two, credibility is not synonymous with resolve. Indeed, scholars have rightly questioned the invocation of credibility as a justification for policy misadventures. “Instead of bolstering one’s credibility,” political scientist Stephen Walt argues, “defending a lot of secondary interests for the sake of one’s future reputation may unintentionally undermine it.” The US decision to escalate the war in Vietnam in the 1960s, as Fredrik Logevall has shown, is one such example. Yet even skeptics do not argue that credibility is unimportant — just that it is too often invoked recklessly.

At the global level, credibility makes alliances and deterrence work, increasing cooperation and reducing the risk of conflict. When major powers possess credibility, the orders that they uphold are perceived as credible by other states, which recognize their own interest in their preservation and therefore willingly operate within them. In contrast, when the credibility of major powers erodes, it creates geopolitical space for new actors, ranging from competitive and opportunistic states to rogue actors and criminal elements. The credibility of the world’s leading powers is thus a prerequisite for the creation and maintenance of international order and geopolitical stability.

As the late US Senator John McCain put it: “Credibility is a nation’s greatest asset in international affairs. It is the hardest to earn and the most difficult to maintain, but once possessed it makes it possible to compel changes in behavior.”

The origins of the credibility crisis

Today’s credibility crisis comes from the two geopolitical powers that dominate the global stage and have been the principal beneficiaries of globalization — the United States and China. The present credibility gap experienced by both the US and China is precipitating the start of a general geopolitical recalibration.

Despite recent efforts to stabilize US-China relations, the most important dynamic currently reshaping the global landscape is the deepening competition between Washington and Beijing. As US President Joe Biden told a joint session of Congress in his first State of the Union address, “We’re in a competition with China […] to win the 21st Century.” Chinese President Xi Jinping, for his part, aims to challenge US “hegemony” and build a “multipolar world” better suited to China’s interests and ambitions.

At the heart of the US-China rivalry is a competition to shape the international order, with each country aiming to demonstrate that it has greater credibility to do so. While US policymakers believe that Washington is “better positioned than any other nation [to] define the world we want to live in,” they also recognize that China “is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and the growing capacity to do it.”

The US and China are competing for global leadership. And given their overwhelming lead in terms of both economic size and military might, only the US and China can plausibly claim the capacity for it. While the European Union is a powerful economic bloc, for instance, it is neither a state nor a significant military actor. The question is whether either Washington or Beijing possesses the credibility to persuade other states to endorse their leadership claims and respective visions for the future of global politics.

The US is the incumbent global leader. As such, it is expected to uphold the global order. But it is increasingly seen by many as unwilling (and, arguably, unable) to do so, at least without a concert of likeminded powers. As the only plausible challenger, China is positioning itself as the principal competitor to the US. But despite its rise, Beijing is increasingly seen by many as unable to do so either.

In this great-power credibility competition, the US and China are not starting from the same position — nor does their credibility (or lack thereof) matter equally for the international order. Given the scale and scope of America’s existing global commitments, Washington’s power is significantly more leveraged on credibility than Beijing’s. And because the US is the incumbent global leader, primary architect, and guarantor of the current international order, its credibility underpins the existing global system to a degree that China’s does not. The trajectory of geopolitical (in)stability accordingly depends far more on the credibility of US threats and promises than those of its strategic rival.

The current system also depends to a significant degree on relations between Washington and Beijing. As the world’s two largest economies, the countries will need to find ways to coexist to maintain global peace and stability. During the summer of 2023, multiple high-level US officials, ranging from CIA Director William Burns to Climate Envoy John Kerry, traveled to Beijing in an attempt to stabilize US-China relations. Those looking for models of cooperation through great-power competition often point to the height of the Cold War — which stayed largely cold thanks to adept statecraft — when the US and USSR partnered to eradicate smallpox, saving tens of millions of lives. For now, despite such efforts and history, similar cooperation between Washington and Beijing appears to be a long way off.

The challenges to US credibility

US credibility has underpinned the post-war global order and the great-power peace we have known for more than 75 years. After the Second World War, the US harnessed its economic and military superiority to rebuild a shattered world, spearheading the reconstruction of Europe and Japan and the creation of international bodies such as the United Nations and the Bretton Woods institutions. Crucially, it drew on its stock of credibility to construct those institutions and persuade other states — including newly independent ones in Africa and Asia — to join them. Even current US competitors have benefited from this system — Fu Ying, who once chaired the foreign affairs committee of China’s National People’s Congress, conceded that the US-led order “has made great contributions to human progress and economic growth.”

During the Cold War, Washington leveraged its credibility to prevent great-power conflict and, under the Truman Doctrine, support nations “resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside powers.” The US established a network of military alliances — most importantly NATO — to deter the Soviet Union. At the core of this containment policy, as its architect George Kennan wrote, was “a test of the overall worth of the United States,” including whether it could successfully manage both “the problems of its internal life” and “the responsibilities of a world power.”

Washington’s record on both counts was mixed. The “city upon a hill,” a beacon of freedom and democracy, coexisted with racial segregation under Jim Crow lasting until the 1960s. That terrible inequality, as well as interventions — both covert and overt — to topple foreign governments, at times undermined US moral leadership abroad. Yet America’s capacity for self-criticism, reform, and rejuvenation meant that when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, US democracy, however imperfect, remained a model for countries around the world.

US credibility as the global leader arguably reached its height in 1991, when Charles Krauthammer observed that the world had entered a “unipolar moment” of unrivaled US dominance. With military primacy, the world’s largest and most dynamic economy, an extraordinary cultural attraction that compelled Joseph Nye to coin the term “soft power,” and widespread international confidence in US leadership and US-led globalization, Washington presided over what some observers later termed a “liberal international order.” America’s AAA geopolitical credit rating allowed Washington to project power widely without risking overextension.

The world has since changed. Three decades later, the US-led order is now being challenged amid intensifying strategic competition with China, geopolitical instability, and questions about the future of US leadership.

Although the US remains the world’s leading power, it is no longer obvious that it can single-handedly uphold and reform the international order it built over the past eight decades. This conclusion reflects not only a shifting balance of power — principally marked by China’s rise as a formidable geopolitical challenger — but also other countries’ concerns about the growing gap between the US’s global commitments and its willingness and ability to follow through on them: namely, doubts about Washington’s credibility.

The developing credibility crisis ailing the US results primarily from two connected factors: recent foreign policy choices and domestic division and dysfunction.

In the last two decades, numerous US foreign policy decisions have alienated both traditional US allies and developing countries in the Global South. The 2003 invasion of Iraq was especially damaging and eroded trust in Washington. The decision not to enforce the “red line” over Bashar al-Assad’s use of chemical weapons against his own people in Syria further eroded the credibility of American power. More recently, US threats to withdraw from NATO reinforced fears about America’s long-term reliability. In the economic domain, Washington’s abandonment of the Trans-Pacific Partnership — a US-led free-trade agreement that would have brought together 12 Pacific Rim countries accounting for 40% of the global economy — undercut its appeal as the commercial partner of choice in the Indo-Pacific.

However, because credibility is context-specific and dispositional, different countries can draw different conclusions about the same policy choices. The US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, for example, and its staunch support for Ukraine since Russia’s 2022 invasion are two recent actions that reshaped American credibility in different ways in different parts of the world.

When the US withdrew from Kabul, many commentators and policymakers saw it as a massive hit to US credibility. Others suggested, however, that the withdrawal could bolster US credibility elsewhere, especially in the Indo-Pacific, by signaling that Washington was serious about reorienting its foreign policy away from a peripheral interest and toward a core one. Washington’s military, humanitarian, and financial aid to Kyiv and wide-ranging sanctions on Russia have had the opposite effect: bolstering its credibility with many advanced industrial democracies, leading some observers to question whether it would take away from its position in the Indo-Pacific, and making some countries in the Global South conclude that US policymakers prioritize European over non-Western interests. In addition, there are international concerns that overuse or even abuse of sanctions by Washington might erode their effectiveness in the short term, and the attractiveness of the US-led financial system in the long term.

Yet the most serious concern undermining US credibility may be what Kennan called the “problems of its internal life.” In recent years, America’s society and political system have become increasingly divided and dysfunctional. Life expectancy has declined as income inequality has grown, and many Americans are not as confident in their or their children’s’ future. Gallup noted in October 2022 that “Americans have as little optimism as they have had at any time in nearly three decades about young people’s chances of having greater success in life than their parents.” Many indicators point to increasing polarization: public trust in the US federal government has fallen to record lows, nearly two-thirds of Democrats and Republicans believe that members of the opposite party are more dishonest and immoral than other Americans, and a small but growing number of Americans — on both sides of the aisle — believes that violence to achieve political results can be justified. After January 6, 2021, it is no longer the case that the US has an uninterrupted history of peaceful transfers of power.

Combined with heightened polarization, the fact that small pockets of the country are shaping big political outcomes makes consensus solutions to the country’s problems elusive. There are fewer swing states and districts in the US, giving members of Congress fewer incentives to compromise. Control of the executive branch, meanwhile, changes from one party to the other, depending on the same narrow group of swing states. This results in foreign policy volatility in the White House and partisan gridlock on Capitol Hill, with Congress regularly slowing or blocking appointments and confirmations. These trends bolster Michael Mazzar of the RAND corporation’s thesis that, today, the US seems “more than any other time in its modern history, to be obstructed from taking decisive action” to address the numerous “intersecting dangers” it faces. Another even more recent example makes the point: when Hamas launched its brutal terrorist attacks on Israel on October 7, 2023, the US had no Speaker of the House and no confirmed ambassadors in Israel, Egypt, Oman, or Kuwait. Senator Chris Murphy highlighted the urgency of the situation: “This is an all hands on deck moment in history.”

Mounting evidence makes clear that domestic politics have eroded America’s global credibility. US allies in Europe increasingly fear that America’s support for both Ukraine and NATO will shift with the domestic political winds. Many of Washington’s traditional partners in the Middle East are growing skeptical about long-term US commitment to the region, prompting some to increase economic and, in some cases, military ties with China. And even in the Indo-Pacific, staunch US allies such as Australia, Japan, and South Korea worry about the reliability of Washington’s commitment to the region. US adversaries, for their part, are looking to capitalize on its domestic dysfunction and undermine its democracy through influence and intelligence operations.

In short, while the US remains the incumbent global leader and retains a great deal of international goodwill, compared to previous decades, Washington’s allies are less sure of its leadership, its competitors are more emboldened, and countries in the middle are hedging their bets.

The challenges to China’s credibility

In contrast to the US, China played a relatively minor role in developing the current international order. Between the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, the Chinese Civil War, the Great Famine, and the Cultural Revolution, it spent much of the 20th century occupied with domestic concerns. Beijing was an important foreign policy actor at important times — notably during World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Sino-Soviet split, the establishment of diplomatic relations with Washington, and through forums such as the Non-Aligned Movement. But it punched below its weight in international politics, given its population and potential.

That context has changed. Since Deng Xiaoping initiated reforms in the late 1970s, China’s economy has grown at the extraordinary reported average rate of 9% annually. It overtook Germany as the world’s largest exporter in 2009, surpassed Japan in economic size in 2010, and has increasingly become a technological peer to the US. More than 800 million Chinese people have lifted themselves out of subsistence-level poverty, and many countries in the Global South now view Beijing as a model of rapid economic development.

The West played a major role in China’s economic rise. Encouraged by its growth and the results of a policy of engagement, US policymakers once even hoped that China would become a “responsible stakeholder.” Washington — and much of the world — shared the goal that Beijing would help “to sustain the international system that has enabled its success.”

Now, however, President Xi has made clear his view that “the East is rising, the West declining.” With its newfound strength, China has launched ambitious programs to remake global politics, including its Global Security, Civilization, and Development initiatives. However, Beijing still casts itself as a developing country when convenient, even as it seeks greater opportunities, leverage, and influence in world affairs.

In recent years, policymakers and observers — especially in the West, but also in places like India, the Philippines, and Vietnam — have expressed growing concerns about the potential implications of China’s strength and foreign policy aims. Chinese Communist Party publications like Document No. 9 have pointed to the need for “struggle” and the dangers of “advocating Western constitutional democracy.” In foreign policy, scholars like Rush Doshi have noted that China has moved beyond Deng Xiaoping’s strategy to “hide capabilities and bide time” and now seeks to “actively accomplish something.”

The aim of these policies is summed up by Xi Jinping’s stated ambition for China to “take center stage in the world.” Since he assumed the role of General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012 and took the helm as his country’s president in early 2013, China has pursued a more assertive foreign policy. There are many examples: Beijing declared an air defense identification zone in the East China Sea in November 2013; deepened its cooperation with Russia after Moscow’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014; and has steadily militarized the South China Sea — including through the development of man-made islands to serve as military bases, which has rattled many of its smaller neighbors in Southeast Asia. Most recently, it embraced a position of “pro-Russian neutrality” over Moscow’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, providing political as well as limited economic and technological support for Russian President Vladimir Putin — alienating many European countries in the process. In 2023, much to the surprise of Western observers, China facilitated the normalization of relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Until recently, there was a widespread view that economic liberalization and ever-greater connectivity with the rest of the world would lead to political liberalization in China. That turned out not to be the case. Today, Xi increasingly appears to prioritize the Chinese Communist Party’s political control over economic growth for the Chinese people. The March 2018 decision of the Chinese National People’s Congress to end presidential term limits — in effect allowing Xi to rule indefinitely — has led scholars to worry about a future succession crisis. Economist Adam Posen has explained how Beijing’s recent actions have “made visible and tangible the CCP’s arbitrary power over everyone’s commercial activities, including those of the smallest players.” As one of us has written, by concentrating steadily more power into his own hands, surrounding himself with loyalists, and eliminating longstanding norms around succession, Xi has made China’s political system more brittle and incapable of self-correcting.

The lack of transparency from the Chinese political system has heightened worries about the prospects for future cooperation on issues that affect both the Chinese people and the world as a whole. For example, World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has been “very disappointed” in China’s cooperation with United Nations investigations into the origins of Covid-19.

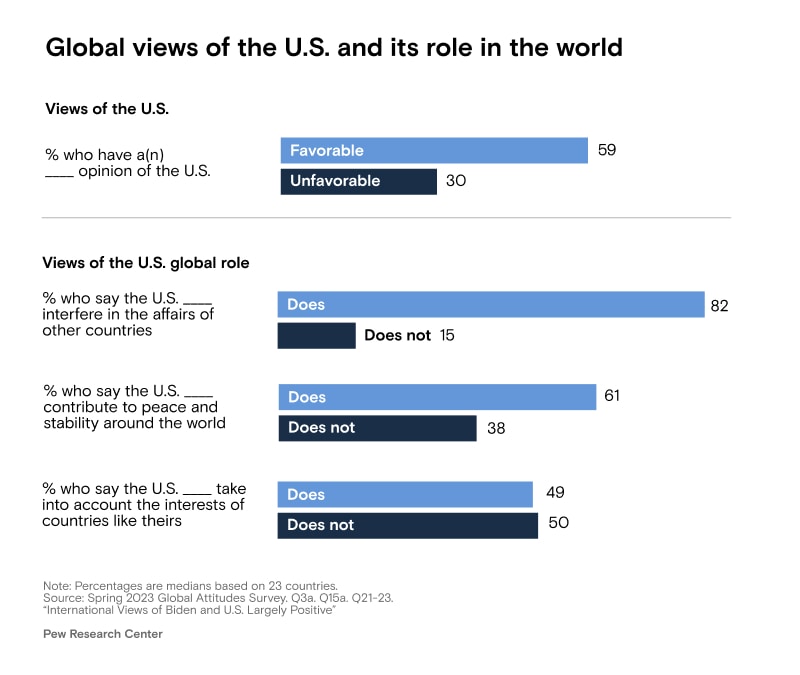

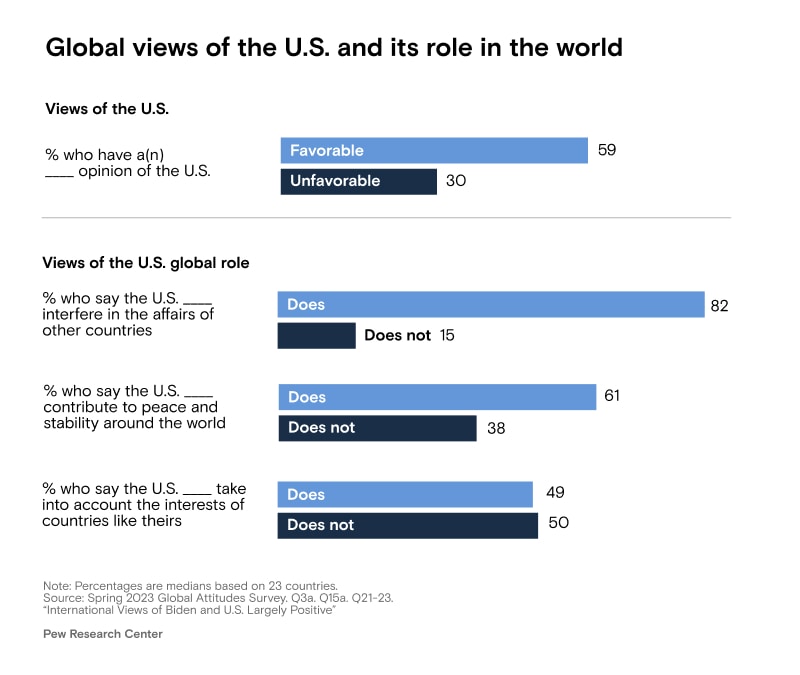

The combination of increased external assertiveness and domestic political control has undermined China’s soft power and dealt a blow to its international credibility. While global public opinion is difficult to measure due to cultural differences, problems of sample size, and methodology, it is clear that negative impressions of China rose sharply around the world in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. To this day, those negative perceptions remain elevated across advanced industrial economies, although views are more positive in Africa and Latin America. According to a July 2023 study by the Pew Research Center, 71% of respondents in 24 countries surveyed believe that China does not contribute to global peace and security. And while its recent global diplomatic outreach campaign is showing moderate signs of success, advanced industrial democracies, as well as developing nations like India, the Philippines, and Vietnam, continue to align closely with Washington despite their concerns about US credibility.

For the first two decades of the 21st century, narratives about China’s rapid growth, development, and modernization boosted its credibility and, in many countries, its appeal as an alternative to US leadership. Now, China is facing questions about whether those narratives still hold, and what role China will play on the global stage.

The US-China competition for credibility

A large driver of the success of the US and China in a more uncertain and competitive global landscape is who is more successful at rebuilding their credibility. It doesn’t help that US-China relations have deteriorated rapidly in recent years. US national security practitioners once imagined that Washington and Beijing could collaborate on constructing “a new model for relations between great powers.” A proposed “G-2” was seen as “imperative if the world economy is to move forward,” and as recently as 2015, the White House National Security Strategy affirmed that “the United States welcomes the rise of a stable, peaceful, and prosperous China.”

Those days are done. The US as well as growing numbers of its allies and partners now see their relationships with Beijing through the prism of strategic competition. The Trump White House declared a new era of “great-power competition” with China, and while the Biden administration prefers the term “strategic competition,” its 2022 National Security Strategy agrees that “the People’s Republic of China harbors the intention and, increasingly, the capacity to reshape the international order.” President Xi, meanwhile, charges that “Western countries led by the US have implemented all-around containment, encirclement, and suppression of China, which has brought unprecedented severe challenges to our country’s development.”

We are not in a new Cold War. But an interconnected world of increased political and even ideological difference is, in our view, here to stay. As is competition between the United States and China. And in this connected but more geopolitically competitive world, there are serious questions about each country’s capacity and, above all, credibility to uphold a truly global order.

The state of great-power credibility

Due to shifts in the global balance of power and the rise of emerging markets, a growing number of observers now contend that the world is either multipolar or verging on multipolarity, a claim that would have massive implications for both geopolitics and the future of trade and investment flows. But there is a simple reason that only the US and China have plausible claims to global leadership: they have the world’s two largest militaries and economies.

The US remains the world’s preeminent economy. At $27 trillion, US GDP accounts for roughly 25% of global economic output — the same share that Washington enjoyed at the end of the Cold War. Many of the world’s leading and most innovative companies, including advanced technology companies, are based in the United States, many of them founded and led by first- or second-generation immigrants whose families sought greater opportunity in the US.

Despite continued speculation about potential alternatives, the US dollar remains the world’s reserve currency by a wide margin. Indeed, as political scientists Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman argue, Washington has grown increasingly adept at leveraging its centrality in financial networks to punish adversaries and induce compliance from allies and partners. This capacity is apparent in the US-led international coalition to impose sanctions on Russia for invading Ukraine — the most extensive enforced against a major power since World War II — as well as agreements with countries like Japan, the Netherlands, and South Korea to impose technology export controls on China.

Yet despite its leading position, the US economy faces challenges that will likely grow more acute over time. America’s national debt reached $33 trillion in September 2023, with interest payments exceeding fiscal year military program spending for the first time through August 2023. The IMF projects that the US economy will grow by just 2.1% in 2023 and 1.5% in 2024. And intensifying efforts on the part of US competitors, as well as some partners, to lessen their reliance on the US dollar, although in their early stages, could reduce its centrality over time; as European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde warned in April 2023, “international currency status should no longer be taken for granted.”

The immense US economy supports its position as the only country that is capable of projecting military power into any corner of the globe; its defense budget — approximately $877 billion in 2022 — remains the world’s largest. With some 750 military bases in 80 countries, moreover, the US enjoys an unrivaled defense network that facilitates its global power projection.

But China is narrowing the gap in the world’s most strategically important region, the Indo-Pacific. While it has not fought a major war since 1979, China has undertaken the world’s “biggest military build-up in peacetime history.” That buildup and modernization began after the Gulf War and accelerated after the 1995-96 Taiwan Strait Crisis. Three decades later, the Pentagon estimates that the PLA is the world’s largest military, with 2.185 million active-duty personnel and a total force of four million. China’s navy is the world’s largest (370 ships and submarines), and it has the largest air force in the Indo-Pacific. The Department of Defense also projects that China could have 1,500 nuclear warheads by 2035, almost four times its current stockpile.

Many of America’s most important allies there have taken note. Australia’s 2023 Defense Strategic Review warns that Washington “is no longer the unipolar leader of the region.” Japan is working to double its defense spending to 2% of GDP by 2027. And the Philippines and the US have expanded their military cooperation. Critically, a growing number of assessments and wargames conclude that there is no guarantee that, if challenged, the US could preserve the status quo in the Taiwan Strait on its own.

Indeed, China is the most formidable, multidimensional competitor that the US has ever faced — a reality most apparent in the economic domain. Beyond having the world’s second largest GDP, China is its largest exporter, the top trading partner for more than 120 countries, and a linchpin for many global supply chains, including for the green inputs that will be essential to enabling and sustaining a global energy transition. Despite an economic slowdown in recent years, many organizations still forecast that China will possess the world’s largest economy before mid-century, potentially seizing a position that the US has held for roughly 150 years.

Yet China’s economy has not met the “Chinese century” predictions that were common until recently. Its GDP is still roughly $9 trillion smaller than that of the US. China remains a middle-income country, with a GDP per capita of just under $13,000 (compared to roughly $76,000 in the US). And there are reasons to believe that the Chinese economy’s slowdown is more structural than cyclical. China’s economic growth declined from 10% in 2003 to 7.8% in 2013; the IMF projects that figure will be 5% this year, and could be as low as 3.7% by 2027.

This economic slowdown — along with the loss of trust in the government over the severe Covid-19 lockdowns — is dashing the hopes of Chinese citizens and fraying the country’s social contract. Youth unemployment in urban areas was 21.3% in June 2023; but the Chinese government has since stopped publishing the figure. As Rick Waters, the US State Department’s former top China policy official, put it, Beijing’s “legitimacy has long been predicated on delivering a sustained rate of growth to the Chinese people in exchange for their accepting its authority.” Now, for the first time in a generation, young Chinese “who came of age when their country’s rise seemed unstoppable increasingly wonder if their expectations will ever be met.”

Though China’s abrupt reversal of its zero-Covid policy at the end of 2022 raised investors’ hopes that the reopening would drive global growth, lower-than-expected results and forecasts have led some observers to wonder if China was showing symptoms of “Japanification,” but at an earlier stage of development that will make it impossible for China to increase total-factor productivity. Perhaps most concerning in the long run, China’s demographic outlook is among the world’s most challenging, with the UN forecasting that citizens 65 or over will outnumber those under 25 by 2040. It is not clear whether China will be able to break free from the middle-income trap over the next decade.

No country can aspire to global leadership without a baseline of hard military and economic power — a necessary but not sufficient condition for a great power to be credible. At the same time, a country that struggles to manage its domestic challenges will struggle to persuade others to view it as an example, let alone to entrust it with the responsibilities of upholding and revitalizing an international order. The US and China have fundamentally different political systems. But they both face crises of credibility in their aims for global leadership.

The international order at stake

As the US and China both grapple with frailties at home and abroad, their competition is intensifying. But while high-level bilateral diplomacy can manage the relationship’s decline, the fundamental direction of travel will not change.

To strengthen its hand, Washington is revitalizing its core alliances and building new partnerships in Europe and the Indo-Pacific, including NATO, the G7, and the Quad. But the conception of a “rules-based international order” often has little resonance beyond advanced industrial democracies. Beijing is countering by strengthening ties with US competitors, making inroads with emerging “geopolitical swing states” (discussed below), and strengthening its trade and investment ties across the Global South. However, it has not gained much traction for its initiatives focused on development, security, and civilization, which are supposed to lay the foundation for a reformed international system.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the US and China are engaged in a global, systems-level competition over which country can more effectively manage its internal challenges, drive an efficient political system to promote growth and stability, and support an international order that others perceive as credible. In this competition, credibility is an input, an arena, and an output all at once.

The consequences of the credibility crisis

Because neither the US nor China is seen as both willing and able to serve as the sole guarantor of the international order, the credibility of the order itself is being called into question, with far reaching implications for geopolitics and global markets. These include: 1) the growing role of geopolitical swing states, 2) the emergence of new alignments and institutions, 3) an emerging technopolar world, and 4) a growing global governance deficit.

1. Geopolitical swing states

The credibility crises facing the US and China, combined with 20 years of emerging market convergence, have led to the emergence of powerful new group of credible global players, the “geopolitical swing states.” These are relatively stable middle and regional powers with their own global agendas independent of Washington and Beijing, as well as the will and capacity to advance those agendas. Today’s crisis in global leadership is increasing risks for these states, but also giving them more room to maneuver. And even absent today’s great-power competition, their economic and diplomatic power make them potent forces in geopolitics.

These geopolitical swing states often pursue heterodox foreign policy strategies of multi-alignment, which allow them to seek partners on an issue-by-issue basis, hedge in the context of the US-China strategic competition, and pursue their own agendas outside the context of great-power competition. The overlapping categories of geopolitical swing states are:

1. Countries with a competitive advantage in a critical aspect of global supply chains;

2. Countries uniquely suited for nearshoring, offshoring, or friendshoring;

3. Countries with a disproportionate amount of capital and willingness to deploy it around the world; and

4. Countries with developed economies and leaders with global visions that they pursue within certain constraints.

India is the paradigmatic example of a geopolitical swing state. Now the world’s most populous country and following a successful chairmanship of the G20 Summit, New Delhi has emerged as a key Western partner through partnerships like the Quad and I2U2 (India, Israel, United Arab Emirates, and United States), as well as through other technology and defense agreements with the US. For many companies looking to diversify their supply chains and investments, including Apple, India is an attractive partner for a “China plus one” strategy, especially given its growing labor force and potential to become the world’s third largest economy by 2030.

But countries won’t always plant their sides consistently alongside one great power or another. While India is an attractive supply-chain alternative and Western partner, New Delhi also continues to engage with Russia. It purchased record amounts of Russian crude oil over the summer of 2023 and Moscow remained India’s top arms supplier well after the 2022 Ukraine invasion. Understanding this complex strategy requires more flexible foreign policy frameworks than the binary of “democracies versus autocracies.” New Delhi’s Minister of External Affairs, S. Jaishankar, has underlined this point, arguing, “Europe has to grow out of the mindset that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems but the world’s problems are not Europe’s.”

India’s strategy of development and multi-alignment has clear appeal throughout the developing world, much of which places great value on sovereignty and foreign policy autonomy. Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister James Marape recently told Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi that the Pacific Island countries consider India to be the leader of the Global South, a position that New Delhi embraces and that puts it in direct competition with China, which has nominally promoted “South-South” cooperation.

Saudi Arabia has also attempted to use its status as the wealthiest Arab country, lead energy producer, and custodian of the two holiest Muslim cities, Mecca and Medina, to secure a greater leadership role in the Global South. Far from seeing each other as rivals, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi have grown closer in ways that position their countries more strategically in the evolving global order.

Over time, geopolitical swing states will continue to have a significant impact on both the global balance of power and the global economy. In the competition over critical minerals, Australia, Indonesia, Norway, Sweden, and many Latin American countries have emerged as key players in the green energy transition. Meanwhile, Norway, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates are using their significant capital, including sovereign wealth funds, to drive global policy agendas ranging from sustainability to infrastructure development — a trend will only grow more pronounced as emerging markets seek new investors in the face of continued questions about the benefits of programs such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The emergence of geopolitical swing states increases the importance of credibility in global affairs. The US and China will each seek to court and thwart these geopolitical swing states to advance their own interests — but neither great power can accomplish its objectives without them.

2. A world of shifting alignments

The global pandemic, war in Europe, and competition with China have started to shift geopolitical alignments into more varied categories — due to factors such as geography, interests, and values — and have accordingly generated new forms of international cooperation in every part of the world. Where existing multilateral arrangements are seen as less credible, or not fit for purpose, new groupings are attempting to fill the void.

There are emerging coalitions of democratic countries around issue-specific domains — notably but not limited to the Quad, AUKUS, the CHIP4, and the US-EU Trade and Technology Council. Legacy multilateral institutions have also expanded their remits to account for new cooperative opportunities. For example, while NATO’s core focus remains on European security, given new urgency by Russia’s war on Ukraine, the nearly 75-year-old alliance is also broadening and deepening its engagement in the Indo-Pacific. The 2023 NATO Vilnius Summit Communique mentioned China 14 times, compared to just once in the 2022 Madrid Summit Communique. Leaders from Australia, Japan, South Korea, and New Zealand (NATO’s Indo-Pacific Partners) also attended the 2023 gathering.

The US, meanwhile, is building new defense cooperation mechanisms in the Indo-Pacific. These include the AUKUS agreement in September 2021 that will help Australia develop a fleet of eight nuclear-powered submarines by the mid-2050s; securing a basing agreement with the Philippines in April 2023; convening a historic trilateral summit with Japan and South Korea in August 2023; and deepening military cooperation with the other members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (better known as the Quad, which includes Australia, India, and Japan).

China is likewise deepening its cooperation with countries like Russia, Iran, and North Korea. But it does not have significant military alliances around the world. While it tries to position some economic forums, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the BRICS, now the BRICS+, as alternatives to Western-led institutions, many countries are wary of this approach and would prefer to focus on their expanded opportunities to practice multi-alignment where possible. In the case of the BRICS, while Beijing is hoping to leverage the forum to increase its global influence, founding members Brazil, India, and South Africa — as well as countries that were recently invited to join, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE — retain close ties with the West.

The trajectory of the much-vaunted Belt and Road Initiative highlights some of the challenges for Beijing’s economic statecraft. In 2019, 37 heads of state came to China for the second Belt and Road Forum to coordinate on Beijing’s signature foreign-policy initiative. But in 2023, only 23 attended. Meanwhile, in September 2023, BRICS+ members India, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE joined the US and several European countries to establish a new economic corridor to integrate Asia, the Arabian Gulf, and Europe, a move perceived by some observers as an alternative to the Belt and Road Initiative. And in the case of the BRICS+, while members agree on increasing the use of local currencies in mutual transactions and empowering the New Development Bank, there are few other areas of concrete policy agreement, and the long-term success of that proposal is uncertain at best.

Where competition is creating new geopolitical alignments, it is also causing new geoeconomic fragmentation, changing how goods and value move around the world. In the competition over global supply chains, Chinese leaders call for “self reliance” and policies such as “Made in China 2025” and “dual circulation.” These aim to reduce Beijing’s dependence on other countries in critical sectors, including technology, and to nurture the growth of independent domestic markets, all while maintaining international dependence on Chinese manufacturers. Western countries are responding by trying to “de-risk” supply chains, focusing on resilience, diversification, and redundancy over economic efficiency. These trends are not confined to Washington, Beijing, or Brussels; developing countries are also pushing toward greater resource nationalism.

This geoeconomic fragmentation is changing the future of the global economy. For example, the green energy transition and increased adoption of digital technologies have put critical minerals supply chains into focus. While there are reserves of critical minerals in varying quantities all over the world, they are processed into usable, constituent materials predominantly — and for some almost exclusively — in China. Geopolitical moves by Beijing to cut off exports of critical minerals to countries as diverse as Japan and Sweden, as well as the United States, coupled with increased resource nationalism around the world over the last decade have increased concerns that these supply chains are vulnerable to shocks and, as US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan warned, “weaponization.”

These concerns have led to the formation of new geoeconomic coalitions. The US-UK Atlantic Declaration would allow UK-sourced components to become eligible for Inflation Reduction Act tax credits, and similar negotiations are in process with the EU and Japan. Meanwhile, the 13-member US-led Mineral Security Partnership is planning 15 potential projects around the world. It is possible that such relationships, if successful, could serve as models for likeminded cooperation for the diversification of other supply chains such as pharmaceuticals.

The economic competition between the US and China may shift from a contest about growth to one about control of critical supply chains. But geoeconomic fragmentation does not mean that globalization is ending, and supply chains that are not sensitive for national security will likely avoid de-risking. At the same time, although national economies remain tightly bound together in transnational and interdependent supply chains, particularly among regional and strategic partners, patterns of globalization are changing, and international trade and investment are becoming more politicized and less efficient. These developments are reshaping how both governments and firms approach economic decision-making in a more fragmented international order.

3. The technopolar order

But it is not only individual swing states and new emerging alliances that have seen their geopolitical agency grow due to the global credibility crisis. The world’s biggest private technology companies are also stepping into the breach to play larger, more autonomous roles in global politics. Many of these companies exercise near-sovereign powers over digital space and are increasingly challenging nation-states as geopolitical actors in their own right.

The diffusion of power and sovereignty away from states and toward tech firms that characterizes this emerging “technopolar” world is both a product and an accelerant of the global credibility crisis. In other words, tech companies are increasingly influential in geopolitics because states are increasingly less so. As tech companies continue to gain geopolitical influence at the expense of states, the global credibility crisis will deepen further. This is exacerbated by the fact that these largely unregulated platforms do not have a natural seat at the geopolitical table, and there is little evidence that, collectively at least, they seek it.

This is a significant transformation of the international system. The Peace of Westphalia enshrined states as the principal holders of sovereignty in 1648, and European powers later extended this system worldwide. Over the past decade, however, a handful of tech firms have come to wield power and influence rivaling that of major states. These non-state actors have effectively become independent, sovereign actors in the vast and growing digital realms they have created and where people increasingly live their lives. As one of us has argued elsewhere, “It is time to start thinking of the biggest technology companies as similar to states.”

Tech companies derive sovereignty not from social contracts or military might, but from their near-absolute control over the data, code, and servers that make the digital world function. Their private decisions directly affect the livelihoods, interactions, and even thought patterns of billions of people globally. They decide much of what people see and hear, determine their economic and social opportunities, and influence what and how they think. This dominance allows them to set rules and exert power in virtual space much like national governments — which have evinced little control over the digital world — do over physical territory. This was already true prior to last year’s public debut of generative artificial intelligence, which will likely only accelerate the trends we have observed.

But it is not only in the digital domain that governments are proving unwilling or unable to exert sovereignty. Tech firms are operating with growing autonomy in the physical world as well. As states’ credibility has eroded, tech companies have come to provide a growing share of the digital and physical infrastructure — from smartphones, telecommunications, and logistics networks to cloud services, e-commerce platforms, and payment systems — that is required to run modern economies and societies. They exert enormous influence over the technologies and services that will drive the next industrial revolution, from 5G networks and automation to semiconductors and AI. Increasingly, they also shape the international environment in which governments themselves operate and determine how countries project economic and military power.

When Russian hackers breached US government agencies and private companies in 2020, it was an American technology company, not the National Security Agency or US Cyber Command, that first discovered and cut off the intruders. When former US president Donald Trump urged his supporters to march on Capitol Hill, where they violently rioted and mounted what then-Senator Majority Leader Mitch McConnell described as an “insurrection,” it was social media companies, not the US Congress, that deplatformed the sitting president to prevent his messages from provoking further violence. And when Russia invaded Ukraine, global technology companies came to Ukraine’s aid, fending off Russian cyberattacks and allowing Ukrainian leaders to communicate with their soldiers on the front lines.

Tech companies’ geopolitical agency will only grow as more of our private, social, economic, and civic life shifts online — and as emerging technologies including AI expand their capabilities and further erode the relative power of governments. Their influence will continue to reach beyond the digital sphere, becoming increasingly powerful stakeholders not only in economics, but also in politics and even national security. Critically, it is unelected, unaccountable, and often unpredictable private actors pursuing their private interests that will exercise this power.

This unprecedented concentration of geopolitical power in the hands of a select few non-state actors is consequential for the future of the international order. Indeed, the balance of power in the 21st century may well be defined as much by competition between tech companies and countries — or among tech companies — as it is by competition between the US and China. Tech companies’ growing influence also suggests that state-centered, 20th-century governance models are becoming inadequate to address the current geopolitical reality. Unless governments become able and willing to design new institutions that include all stakeholders, the world will become much harder to govern. As more countries and companies gain more technological capacity, this will only become more difficult.

As the global credibility crisis grows more entrenched, tech firms and their leaders will have increased power to shape the world around them. How these new geopolitical actors choose to wield their power — and what powerful countries do in response — will go a long way in determining whether the international order will be able to escape its credibility crisis or be consumed by it.

4. Global governance deficit

Perhaps the clearest outcome of the great-power credibility crisis is the erosion of international cooperation on urgent transnational challenges that require collective action, from pandemics to climate change to mitigating the risks and seizing the opportunities of disruptive technologies. These issues affect the global commons and cannot be adequately addressed by individual countries acting alone.

International cooperation is hard enough to achieve at the best of times. Although global public goods benefit everyone, coordination failures tend to result in their under-provision. Because global public goods are costly to provide but available to everyone once produced, every country has an incentive to “free ride” on the efforts that the rest of the world makes while still sharing in the benefits. And because every country makes the same calculation, the result is that the world typically fails to do enough to provide these goods.

The textbook solution to this problem is coordination, whereby countries are incentivized to invest in collective action by credible commitments that others will do so too. However, coordination requires countries to trust that others will keep their commitments. The global credibility crisis has eroded that trust and worsened the collective action problems inherent to the provision of global public goods. Although addressing transnational challenges is in every country’s long-term interest, the diminished credibility makes countries more reluctant to limit their own sovereignty by accepting binding rules and making costly investments. The result is a global governance deficit — a mismatch between the proliferation of cross-border issues affecting the global commons and the increased reluctance or inability of countries to come together to address them.

This problem was evident during the Covid-19 pandemic, when geopolitical rivalries, weakened international institutions, and beggar-thy-neighbor policies led to shortfalls of critical medical equipment and major disparities in the global distribution of vaccines. It also underpins the world’s collective failure to address climate change and biodiversity loss, which are already having major consequences across a range of sectors and issues, from agriculture and finance to food security and refugee flows. While individual countries, including the US, and the global community have made significant progress on climate action, the chronic under-provision of climate financing for developing economies by advanced industrial economies — despite their commitment in 2015 to provide $100 billion annually — is a testament to the lack of credible international coordination on this issue.

The emergence of new and disruptive technologies including generative AI further highlights the growing global governance deficit. AI systems hold immense promise but also pose great risks, from automated disinformation and algorithmic bias to job displacement, weaponization, unintended military escalation, and even loss of human control. The technology’s complexity and the speed of its adoption and advancement will make containment impossible. Effective AI governance would require unprecedented coordination between countries and tech companies to create new mechanisms and institutions that match the technology’s unique features.

The credibility crisis makes the necessary governance innovation and cooperation much more difficult. States lack the technical expertise and bureaucratic agility to govern AI adequately. The most powerful national actors — the US and China — fear falling behind their competitor in an AI arms race, and are accelerating AI development, rather than slowing it down. Meanwhile, private tech firms have misaligned incentives for self-regulation and no official role in the AI governance process, even though they are the principal agents of power in the AI space. All these factors inhibit collective action. Without renewed, credible leadership that enables urgent global cooperation, unconstrained AI proliferation will further destabilize the international order.

Conclusion

We argue that credibility is a key variable for evaluating a country’s ability to effectively project power, drive growth, and influence outcomes. Assessing the credibility — or lack thereof — of the world’s leading powers, in turn, provides important insights into the dynamics that currently drive geopolitical volatility and instability worldwide, and that will continue to shape the world order for years to come.

Understanding great-power credibility requires more than analyzing quantitative measures of strength such as GDP and military spending; it also takes history seriously as well as the question of how other countries perceive the influence that leading powers wield. Credibility flows not only from the capabilities at countries’ disposal, but also from the degree of trust and predictability they exercise in deploying those capabilities. In a world where great powers and the international order that they uphold enjoy and exercise credibility, other countries recognize their own interest in working with those powers and within that order. But when great-power credibility erodes, so too do the incentives for countries and other actors to respect established rules and conventions, intensifying geopolitical competition and destabilizing the international order as a result.

The US has not lost significant power in recent years, but its credibility has diminished, whereas China has gained significant power but not the credibility to match it. Both countries suffer from a significant and growing credibility gap. Today, we are facing renewed instability in the Middle East, a raging war in Europe, and mounting tensions in the Indo-Pacific converging to produce the most unstable geopolitical environment since the end of the Cold War. There are technological changes taking place that will reshape our world in ways we are only beginning to understand. And no single great power is both willing and able to uphold, renew, and sustain the kind of international order that will be required to navigate and steady our changing world.

Understanding the world as it is requires leaders in every sector to plan, adapt, and ask fundamental questions about how the shifting international order will affect businesses and markets. How can they assess what actions particular countries will or will not take to secure their interests and how other countries will respond? Under what circumstances might countries engage in policy overreach as they attempt to advance their objectives? When will they lack the ability, will, and/or buy-in to build coalitions in pursuing those goals? And how can leaders identify likely outcomes, defend against risks, and take advantage of opportunities in a fast-changing global environment?

The credibility lens is an effective way for businesses to view a changing geopolitical order and help understand how established and emerging actors are shaping economic and geopolitical outcomes in their favor. The age of great-power competition is also the age of geopolitical swing states, shifting geopolitical alignments, the new technopolar order, and the deepening global governance deficit. As we face an uncertain, turbulent era of global politics, the credibility lens will help political and business leaders alike chart their paths with greater clarity and conviction.

This article has been prepared by Goldman Sachs Global Institute and is not a product of Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research. This article is being provided for educational purposes only. This article does not purport to contain a comprehensive overview of Goldman Sachs’ products and offerings. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and may differ from the views and opinions of other departments or divisions of Goldman Sachs and its affiliates. The information contained in this article does not constitute a recommendation from any Goldman Sachs entity to the recipient, and Goldman Sachs is not providing any financial, economic, legal, investment, accounting, or tax advice through this article or to its recipient. Goldman Sachs has no obligation to provide any updates or changes to the information herein. Neither Goldman Sachs nor any of its affiliates makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of the statements or any information contained in this article and any liability therefore (including in respect of direct, indirect, or consequential loss or damage) is expressly disclaimed.

Subscribe to Briefings

Our signature newsletter with insights and analysis from across the firm

By submitting this information, you agree that the information you are providing is subject to Goldman Sachs’ privacy policy and Terms of Use. You consent to receive our newsletter via email.