The War in Ukraine Stokes Global Food Inflation

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has heightened the uncertainty over food supply, a global market that was already feeling the effects of COVID-19 and the ongoing impact of climate change.

At this year’s World Economic Forum, the head of the World Trade Organization Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala warned that a food crisis could last two years unless safe corridors are created to move Ukrainian food stocks. With the help of Goldman Sachs Research, we took a closer look at the regions most affected by surging food prices and the increasing cost of agricultural commodities and products.

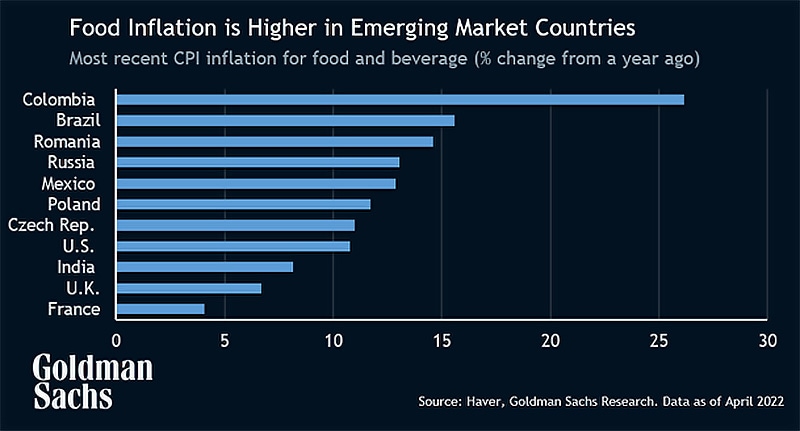

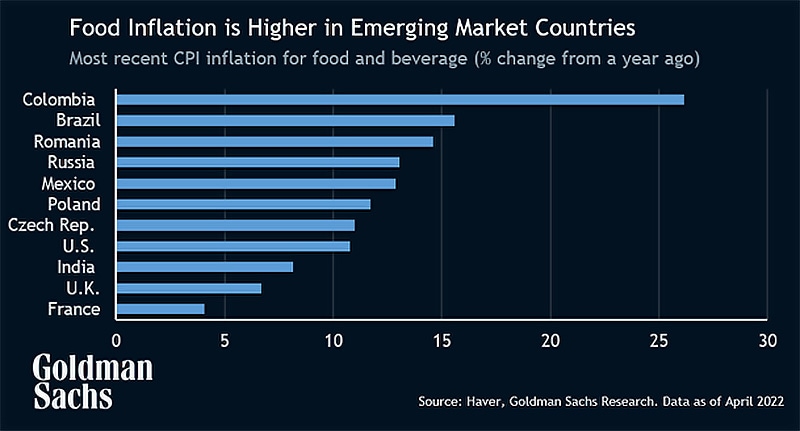

Yulia Zhestkova, who has analyzed global food inflation for Goldman Sachs Research, notes that key drivers of food inflation – including unfavourable weather conditions, higher input costs and pandemic-driven disruption – were already in place before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Zhestkova says that the shocks are concerning for emerging markets, which are more susceptible to threats on food security. Here, a high proportion of consumer income is spent on food, so even a marginal increase in food inflation might hit households in these regions particularly hard.

“Food inflation is definitely being felt in a lot of countries in the CEEMEA region, like Turkey, but also in eastern Europe, in nations including Romania, Poland and Hungary. All of them are enduring meaningful surprises to the upside,” Zhestkova explained. “We have also seen a significant surge in prices in the big LATAM countries, like Brazil, Argentina and Mexico.”

Before the war in Ukraine, food inflation was increasing worldwide. Now the conflict is compounding the crisis. According to Goldman Sachs research, Ukraine and Russia account for more than 20% of global wheat and oilseed production. This has been disrupted by the war, with the combined dry bulk shipping activity from the region dropping by 40% compared with the 2021 average.

“March and April are when farmers are going to the fields and working on their summer harvests,” Zhestkova says. “For the first two months of war we haven’t seen any grain shipments coming from Ukraine, and although Ukraine has managed to return about 15-20% of exporting capacity since, the lack of fertilizers and general disruptions are hitting Ukraine’s grain harvest now and will drag the crisis on into the next year.”

As a result, many of the countries already feeling the impact of surging food costs are now feeling the effects of the conflict in Ukraine. Those nations that import soft commodities from Ukraine and Russia are the most obviously affected, according to Zhestkova, and alongside European neighboring states, these include large CEEMEA countries such as Turkey and Egypt, and in Africa, Nigeria and Sudan.

Countries in South America are also feeling the effects — albeit in a different way. Countries here are impacted primarily through inputs of agriculture production. “There has been a slow decline of fertilizer exports from eastern Europe,” Zhestkova says. “The price of fertilizers has increased 2.5 times since May 2019. Though this is the first year when the farmers are dealing with such extraordinarily high prices, and a contributing factor is that LATAM farmers rely on fertilizers produced in Russia and Belarus.”

Zhestkova believes the full effects on food prices from the war in Ukraine are yet to be felt. “I think most of the impact is still in the pipeline,” she concludes. “Low harvests, problems with supply chain distribution, and elevated input prices across the world were putting pressure on global food inflation to the upside. We now have added pressure on supply because there is a loss from the unharvested fields in Ukraine.”

Our signature newsletter with insights and analysis from across the firm

By submitting this information, you agree that the information you are providing is subject to Goldman Sachs’ privacy policy and Terms of Use. You consent to receive our newsletter via email.