Why the CHIPS Act Is Unlikely to Reduce US Reliance on Asia

The recently passed CHIPS Act earmarked $39 billion in U.S. federal funding to build chip manufacturing facilities in the US. While it might serve as a valuable hedge against future supply chain disruptions, it’s not likely to make a dent in supplanting Asia’s dominance in the sector, according to Goldman Sachs Research.

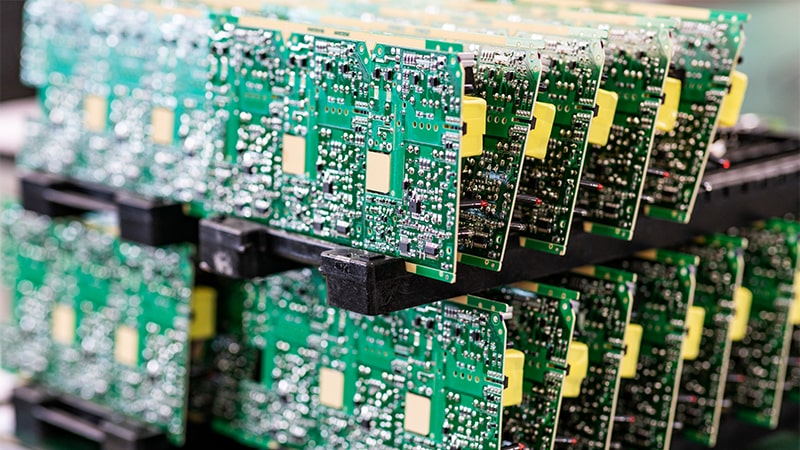

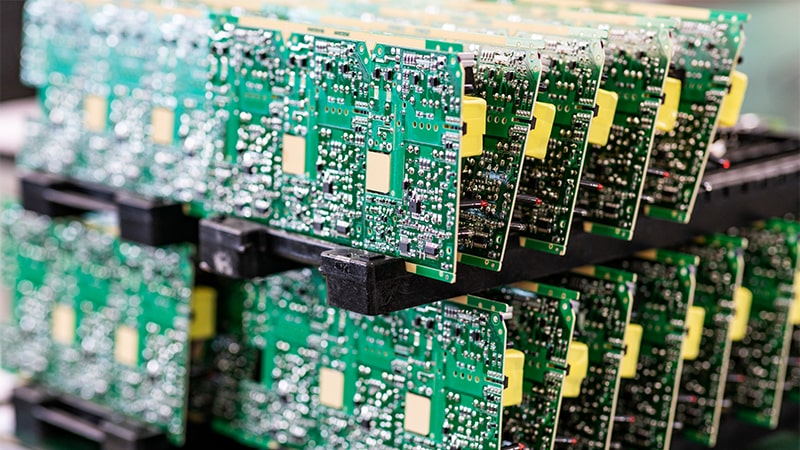

The pandemic-fueled global supply chain dislocation woke many up to the realization that semiconductors power almost everything—cars, cellphones, washing machines, refrigerators, and so on. When global supply chains ground to a near halt during COVID-19, manufacturers’ access to chips, and thus consumers’ access to a wide range of products, became scarce.

Demand for chips is expected to accelerate, according to GS Research. Megatrends such as 5G, electric vehicles, artificial intelligence and high-performance computing has positioned global semiconductor revenue growth on an even steeper trajectory than it has been on in the past several decades.

Of critical importance is the issue that most of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing capacity is based in Asia. The region serves as the production hub for between 75% and 80% of global chip manufacturing – mainly from companies based in Taiwan, South Korea, mainland China, and Japan, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association and BCG. Asia’s dominance has come at everyone else’s expense: In the US, the share of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity has dropped to 12%, down from 37% in 1990. In Europe, the decline has been even more precipitous: 9% in 2021, down from 44% in 1990. That left both regions vulnerable when the pandemic caused supply chain disruptions throughout Asia, and prompted the U.S. Congress to pass the CHIPS Act to shore up domestic manufacturing capacity.

Except the funding allotted at this stage is expected to fall short at this stage says GS research. Why? Production costs, for one. In the US, it’s significantly more expensive (44% higher) to build and run a new fab than it is in Taiwan, according to the analysts. Out of that 44% premium, 21% is coming from higher capital expenditures in the US than in Asia, 18% from higher operational costs over a 10-year period and 5% from operational inefficiencies tied mainly to culture, operation and management style differences, and other factors.

The CHIPS Act will help boost production, but GS Research says the current incentives in the Act will only be able to ‘fully’ support an increase in the U.S.’s market share of global chip capacity of less than 1%. That’s because the industry’s capital expenditures will continue to trend up as we move towards more advanced technologies, and that capex is expected to double over the next three years and surge by a 17% compounded annual rate of growth, compared to just 8% over the past decade, according to GS Research forecasts.

GS Research concludes that the CHIPS Act will help create a domestic pressure valve when future supply disruptions occur, but much more funding will be needed to reshape the global semiconductor industry. “We believe the CHIPS Act should be viewed more in the context of US geopolitical strategy, ‘hedging’ against future crisis or major supply chain disruptions rather than efforts to replace Asia’s current position and importance within the semiconductor supply chain,” the authors wrote.

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that the CHIPS Act will supply $53 billion in U.S. federal funding to build chip manufacturing facilities in the U.S. This has been updated to reflect that $39 billion of the $53 billion bill will be used for this purpose.

Subscribe to Briefings

Our signature newsletter with insights and analysis from across the firm

By submitting this information, you agree that the information you are providing is subject to Goldman Sachs’ privacy policy and Terms of Use. You consent to receive our newsletter via email.