How to Overhaul the Tried-and-Tested Investment Portfolio When Inflation Soars

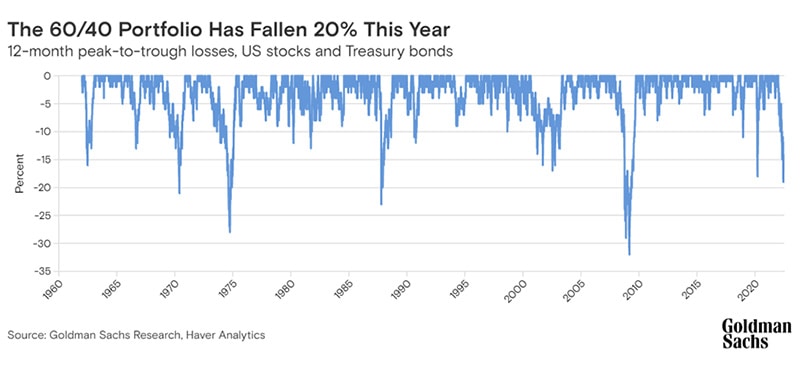

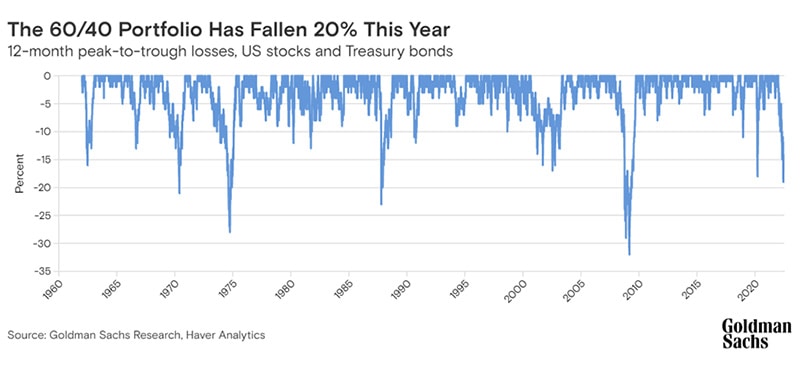

The tried and tested 60/40 formula for buy-and-hold investment portfolios got off to its worst start since World War II.

The 60/40 portfolio — split between the S&P 500 Index of stocks (60%) and 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds (40%) — fell about 20% in the first half of 2022, the biggest decline on record for the start of a year, according to Goldman Sachs Research. Such ‘balanced’ portfolios, meant to blend the higher risk of stocks with the relative safety of government bonds, often have different formulations, such as a mix of corporate credit or international stocks. But virtually all of them had one of their worst starts to a year ever, according to Christian Mueller-Glissmann, head of asset allocation research within portfolio strategy at Goldman Sachs.

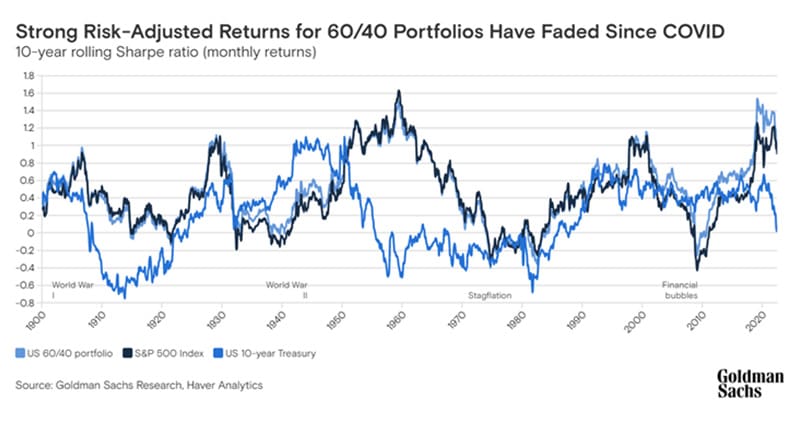

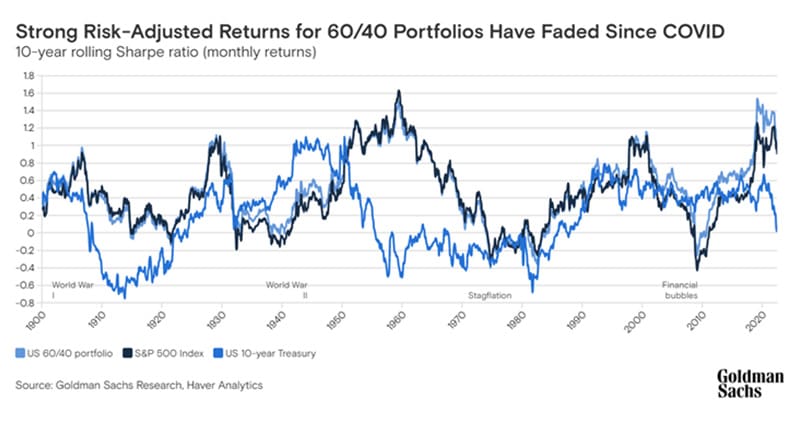

Almost all assets were in a precarious position at the start of the year, as valuations for stocks and bonds were hovering around their highest levels in a century, Mueller-Glissmann says. Decades of tame inflation allowed central banks to drive interest rates ever lower to try to smooth out the business cycle, which in turn pushed assets from stocks to house prices higher. In fact, in the decade before the COVID-19 crisis, a simple U.S. 60/40 portfolio delivered three-times its long-run average for risk-adjusted returns.

And then 2022 hit. As consumer prices and wages accelerated, central banks like the Federal Reserve scrambled to reverse their policies. That resulted in one of the biggest ever jumps in real yields (bonds yields minus the rate of inflation). As policy makers try to contain skyrocketing inflation, stock investors are increasingly concerned that those efforts will slow growth, potentially tipping large economies like the U.S. into recession. Indeed, investor concerns have recently shifted from inflation to recession concerns as soaring inflation expectations have fallen, but it might be too early to fade inflation risks, at least in the medium-term, says Mueller-Glissmann.

“In contrast to the last cycle, you’ve had a mix of growth and inflation conditions that are quite unfriendly,” Mueller-Glissmann says. Rising inflation weighs on bonds, as does monetary policy tightening (when central banks increase interest rates). This also means weaker growth, meanwhile, which is a headwind for equities, and equity valuations suffer from rising rates as well. “That is a backdrop that’s very bad for 60/40 portfolios, irrespective of valuations,” he said.

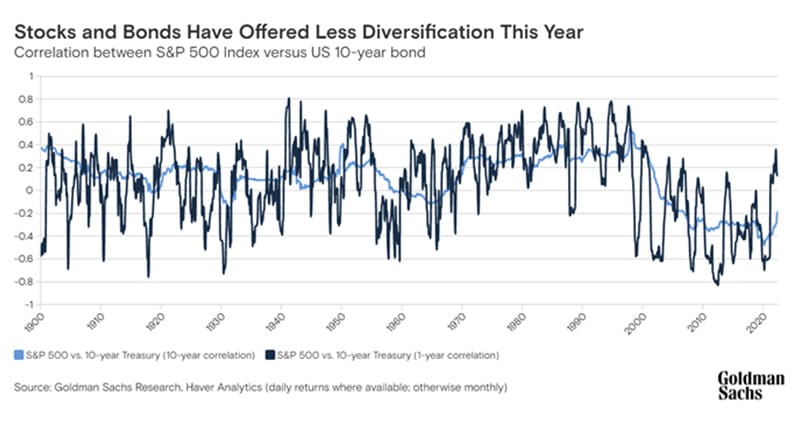

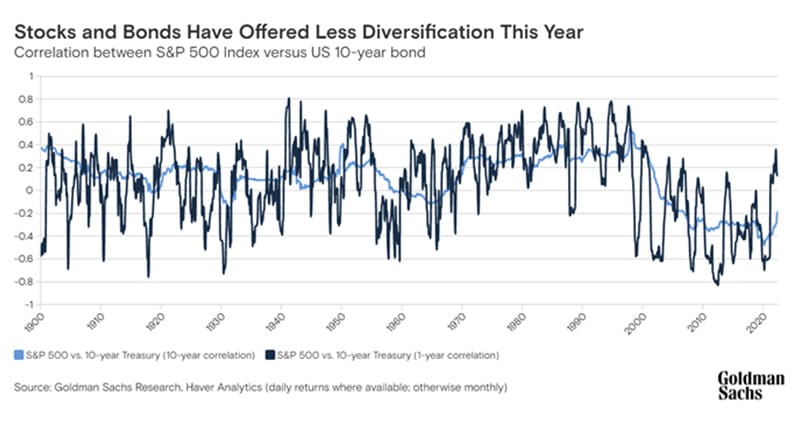

That means there’s less diversification potential between equities and bonds, as they have been more positively correlated this year — in fact this has been more often the case than not historically.

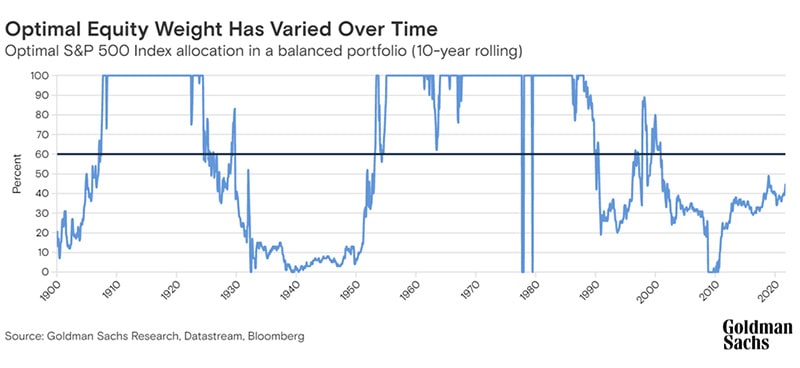

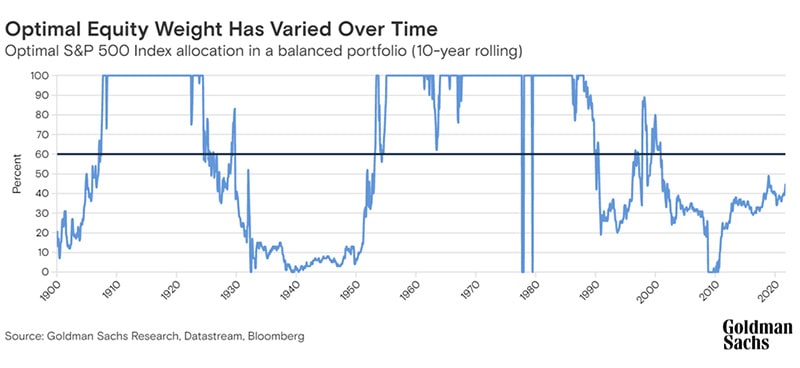

A funny thing about the 60/40 portfolio is that nobody really knows where it comes from. While it’s a popular benchmark, Mueller-Glissmann points out that it wouldn’t be right for everyone. A person close to retirement might want a larger proportion of their savings in bonds, for example, while someone investing at the start of their career would probably want to buy more stocks.

The 60/40 may still make sense as a starting point for asset allocation. It has been the optimal ratio on average since 1900 to maximise the risk-to-reward for a portfolio made up of only stocks and bonds (although the optimal allocation to equities has varied materially over time depending on broader macro conditions), Goldman Sachs Research shows.

The outlook for the 60/40, however, might not improve right away, as long as inflation is percolating up and central bank tightening weighs on growth. “I don’t think it’s dead, because the current environment won’t last forever, but it’s certainly ill-suited for that type of backdrop,” Mueller-Glissmann says. “In an environment where you have both growth risk and inflation risks, like stagflation, 60/40 portfolios are vulnerable and to some extent incomplete. You want to diversify more broadly to asset classes that can do better in that environment.”

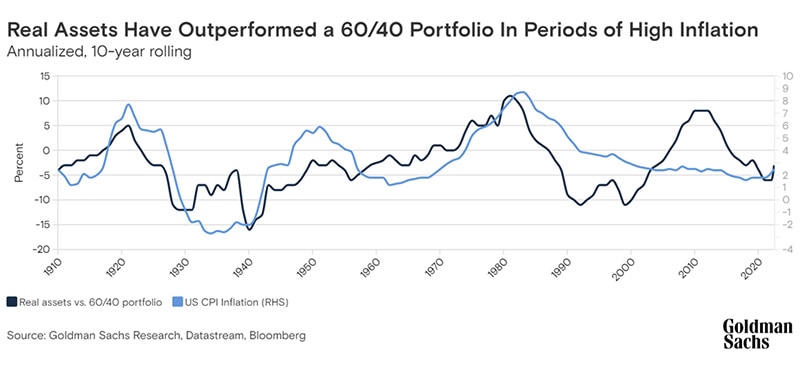

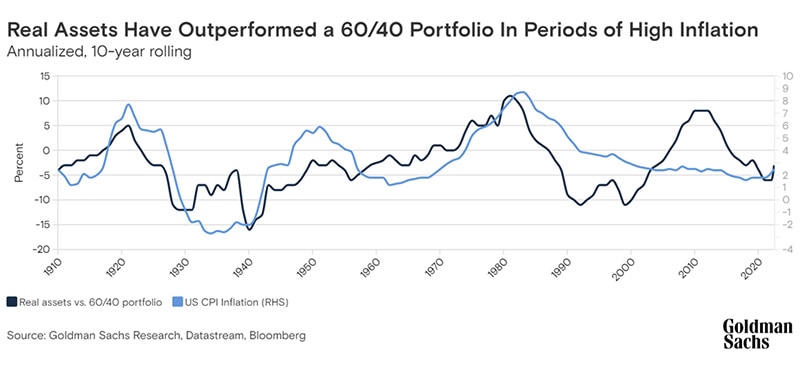

Real assets could be more important in a cycle where inflation is higher than the world has been used to over the past two or three decades. Things like residential real estate can generate profits that exceed inflation. Precious metals and even fine art and classic cars can help protect purchasing power when consumer and commodity prices are climbing quickly.

A portfolio with a slice of real assets, like gold and real estate, performed even better than the 60/40 over the long run. In that case the optimal strategic asset allocation since World War II was closer to one-third equity, one-third bonds and one-third real assets, Mueller-Glissmann says.

“I think that’s a better starting point as compared to 60/40, with everything we know right now, with potentially higher structural-inflation pressures due to decarbonization, deglobalization and the fight on income inequality,” Mueller-Glissmann says. He points out that there are also stocks that can have the characteristics of real assets, such as companies that have pricing power and the capacity to grow cash flows at a rate that exceeds inflation.

Investors can also consider assets that fight inflation. “Automation is an example, if you find business models that benefit from structural growth because of higher inflation,” he said. “There’s plenty of opportunities that come about because of this new world where we have more inflation and more inflation uncertainty. But the most important thing is they are very different from what we saw as the best investment of the past 20 to 30 years.”

Investors have picked up on this shift. Instead of a tech startup that might not produce a profit until many years from now, investors are favoring companies that can already produce earnings and dividends. Warehouses have been a popular investment as e-commerce accelerates. Demand for companies that make battery storage has grown amid an increasing focus on renewable energy infrastructure.

But as recession risks rise, some real assets have also become more volatile in recent months. Nobel prize winning economist Harry Markowitz is credited with saying that diversification is the only free lunch in finance. Mueller-Glissmann says that principle applies to investing in real assets as well. They tend to be heterogeneous, with different risks.

Real estate investment trusts (REITs), for example, tend to keep up with inflation in the long run, but they’re highly leveraged and perform poorly during a recession. Infrastructure, such as a company that operates an airport or a sewage system, might have steady cash flows from government contracts. But there’s still a risk that company could be hit with new tax charges or regulation. And while commodities like oil and grains are essential basic needs, their prices tend to be extremely volatile when there are imbalances between supply and demand.

“You want to have a bit of diversification within real assets as well,” Mueller-Glissmann says. Goldman Sachs Research has run the numbers and found that a roughly equal weight (about 25% in each) between real estate, infrastructure, gold and a broad commodity index has led to the best risk-adjusted performance in periods of high inflation. Allocations to Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), which were created in the late 1990s and are a more defensive real asset, can help lower cyclical risk while providing inflation protection.

Going forward, active portfolio management, allocations to alternative assets — such as private equity but may also include hedge funds — and new strategies for mitigating risk, like option hedges, are going to be more important in multi-asset investing, Mueller-Glissmann said.

“I would disagree that diversification is the only free lunch in finance,” he added. “But certainly it remains a core investment principle for any investor.”

Subscribe to Briefings

Our signature newsletter with insights and analysis from across the firm

By submitting this information, you agree that the information you are providing is subject to Goldman Sachs’ privacy policy and Terms of Use. You consent to receive our newsletter via email.